By David Dodge and Duncan Kinney

Christine Wörlen, a Berlin-based consultant and former head of renewable energies for the German Energy Agency speaking in 2011 in Edmonton, Alberta.

Energiewende – pronounced phonetically as “en-er-gee-ven-da,” is the German word for the energy transition that’s been happening in Germany for the past 25 years. This developed, industrialized country with a large export economy is successfully and aggressively transitioning away from fossil and nuclear to renewables.

In 2014, more than a quarter of all German electricity came from renewable sources. Combine all the renewable energy sources together and it’s the single largest piece of Germany’s electrical energy pie.

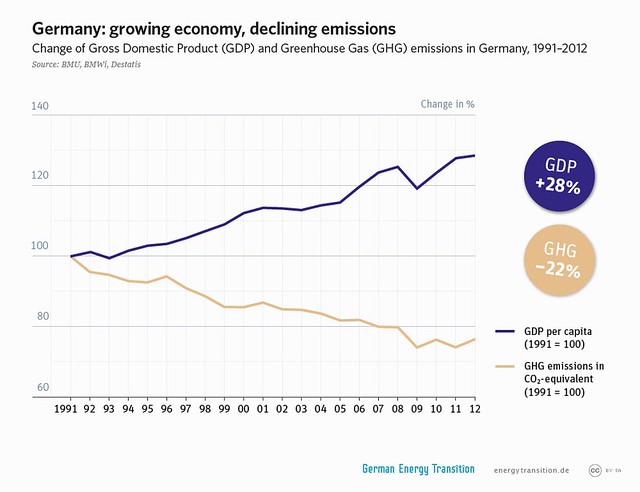

Renewable energy capacity has increased seven-fold since 1991 while GDP has grown 28 per cent over the same time. Greenhouse gas emissions have been reduced by 22 per cent during the same period. Even more surprising Germany has relatively poor renewable energy resources. They don’t have the blazing sun and wind of the prairies or our massive hydro and biomass resources.

This rapid pace of change threatens business as usual and has attracted critics armed with arguments that aim to belittle and besmirch Germany’s energy transition.

“When I travel through Canada or the States I see a lot of information that is really, really wrong. That is just technically wrong,” says Christine Wörlen, a Berlin-based renewable energy consultant and the former head of renewable energies for the Germany Energy Agency.

“Like when you listen to Fox News saying it can only deploy so much solar power because the solar regime in Germany is so much better than the United States. That’s just you know, against the laws of physics.”

Germany is about as sunny as Alaska.

Reliable renewables

A common myth about Germany is that due to all that intermittent solar and wind energy on their grid that they must be constantly suffering from rolling blackouts.

It turns out you should never underestimate German engineering.

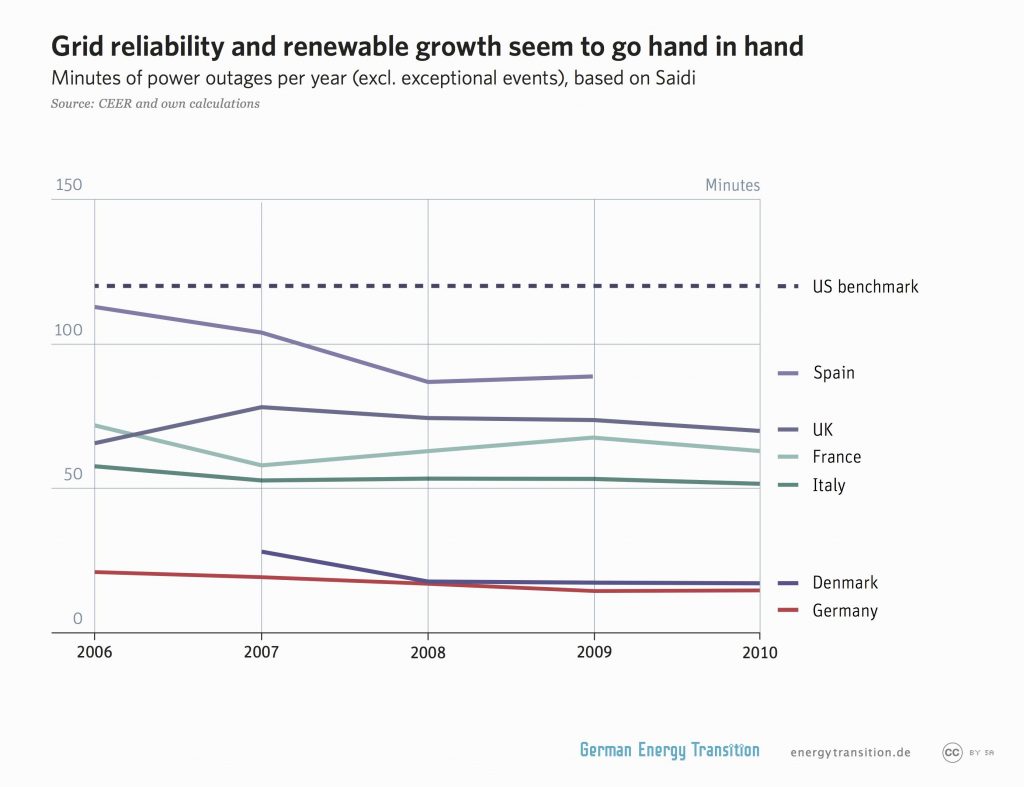

“There is an international comparison or benchmark that measures the average time of how often the grid is in blackout, the average minutes per year. Germany has roughly 15 minutes per year when the grid is in blackout,” says Arne Jungjohann, a Stuttgart-based strategic advisor on policy and politics who’s worked in the German parliament, in Washington D.C. and in German state politics. “Other countries like Italy and France have 50 minutes per year. The United States does not even have this kind of data available but they have set a benchmark of 120 minutes a year which would be okay for the grid to be offline.”

Energiewende, or the energy transition in Germany has produced rapid growth in renewable energy and one of the most reliable electricity grids. Figure: http://energytransition.de/

“It seems that Germany’s electricity system is one of the most reliable energy grids in the world,” says Jungjohann.

Germany’s energy transition is also a mainstream, popular affair. The centre-right government of Angela Merkel adopted the term in 2010 and its popularity can be partly explained by a simple fact: regular Germans are involved and making money off of it.

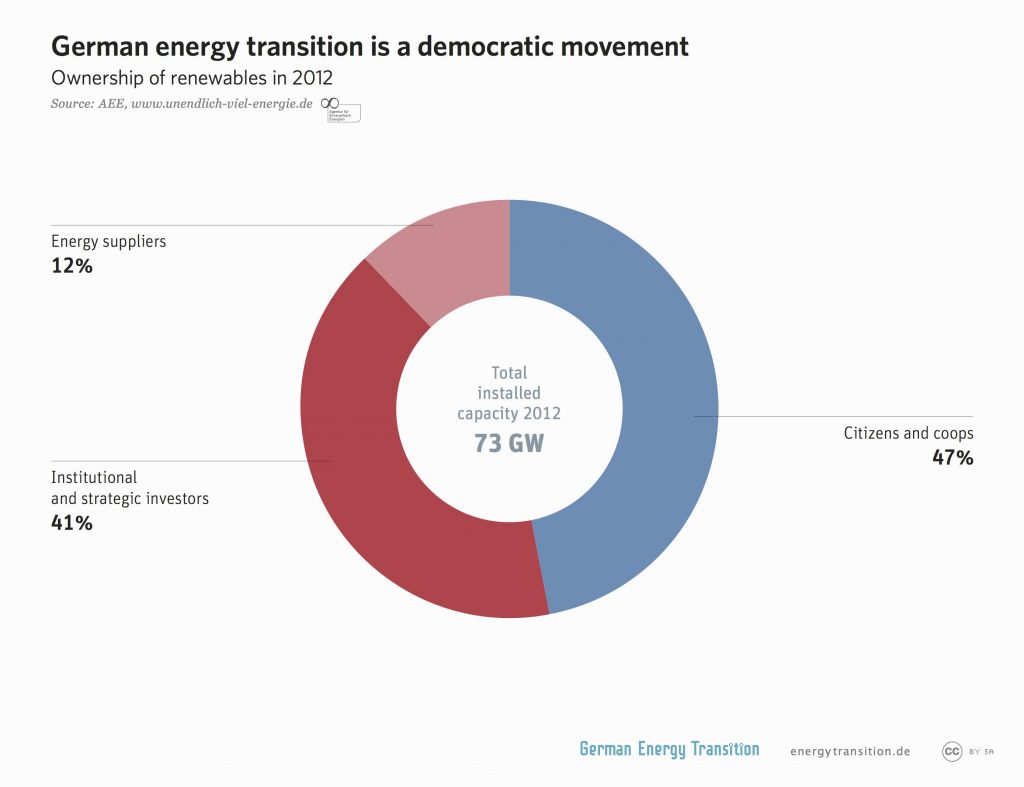

“We see that in Germany a lot of citizens invest in wind parks, solar panels, biogas plants — that is something that is unique compared to other countries and the reason for this was the policy was set up so that the little guy can compete with the big guy,” says Jungjohann.

By giving farmers, citizens, co-operatives and municipalities a leg up on accessing Germany’s very successful and very aggressive feed-in tariff program, they were able to spread the benefits and investment of the transition around and ensure broad political support. Citizens and co-ops own 47 per cent of German renewables.

The German energy transition has has achieved broad support by involving citizens and coops as investors and owners in the renewable energy industry. Figure: http://energytransition.de/

The feed-in tariff, which guarantees grid access and a fixed price for renewable energy that’s produced, means that the average German pays more for their electricity than an average North American. But according to independent energy analyst Chris Nelder, that fact doesn’t appear to have had much of an effect on the German economy, which has maintained strong growth through the entire period.

“The wild claims that Germany’s energy transition would drive the manufacturing industry out of Germany and destroy their industrial base and all that — none of that ever came to pass. They might have paid more for solar in the early part of the transition but it hasn’t really hurt their economy as far as I can see.”

GDP in Germany has grown at pace and the price of alternative energy such as solar has declined significantly.

Of course not everything is perfect. Germany did see a small uptick in electricity from coal in 2013 mostly for export purposes. And that number has gone down in 2014. Jungjohann wishes the Energiewende had also focused on transportation fuel and heating as well.

But the best part about Germany’s energy transition, the part that affects you and me here in North America, is how much the costs have been driven down for renewable energy. It was German demand that spurred a massive worldwide build out of solar PV manufacturing capacity. Now wind and solar are competing, and winning, on price against conventional fuels.