By David Dodge and Duncan Kinney

When I first heard of “run-of-river” I had it way wrong, I imagined a thousand little micro-turbines in a mountain creek turning like pinwheels as the water flows by.

It’s more of a kinder, gentler version of bigger hydro power projects – none of the flooding of massive tracts of land.

Don Gamache of Innergex was our helpful guide. Sporting a mountain man beard, 4×4 truck and plenty of warm clothes he’s the plant operator for the Fitzsimmons Creek run-of-river project and two other nearby run-of-river projects.

For Gamache it’s a dream job. He gets to spend time outside in the mountains, enjoying the fresh air and tooling around on snowmobiles to ensure that these multi-million dollar machines run like clockwork.

The Fitzsimmons Creek project is a 7.5-megawatt power plant right in the Whistler Blackcomb ski resort and it produces enough power to cover the annual energy consumption of the site. Not too bad when you consider its 38 lifts, 17 restaurants, numerous snow-making machines and other buildings and services.

And it’s hard work. It’s only Gamache and one other full-time employee (along with two part-timers) who wade through hip-deep snow to check water intakes, monitor oil levels and do the ongoing preventative maintenance that must be done to ensure that a multi-million dollar machine doesn’t smash itself to bits.

Don Gamache, operator of the Fitzsimmons Creek run-of-river project, gestures at the weir where water is diverted into a penstock pipe that travels 3.5 km down to the power plant. This headpond is sandwhiched between Whistler and Blackcomb mountains. Photo David Dodge

Gamache has a patient, fatherly tone as he goes over how it works. It turns out that run-of-river doesn’t involve micro-propellers in streams at all, not even close.

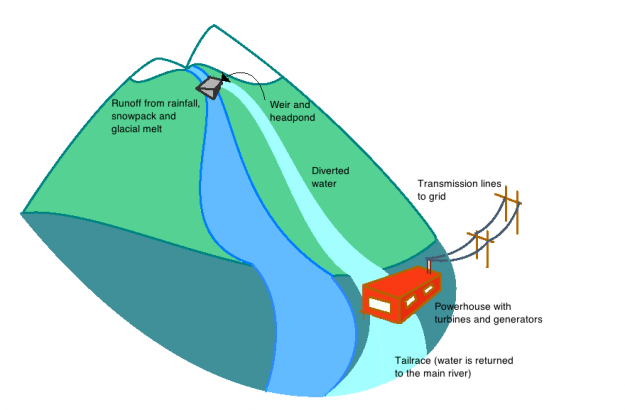

You divert a portion of a river, stream or creek that has a lot of elevation change, into a pipe. You take that pipe and run it several kilometers downhill to a powerhouse where, with an assist from gravity, you use the force of the water to spin a turbine and generate electricity. At Fitzsimmons creek there is a 250-meter elevation change (what’s called head) and the pipe travels 3.5 kilometers downhill from where it’s diverted to the powerhouse. That builds up a lot of pressure. When the water in the pipe finally gets to the powerhouse the water is at 350 psi.

Diagram courtesy of Charlotte Heston and Energy BC

Big business for small(er) hydro

Run-of-river is growing fast in British Columbia. There are currently 45 different operations totaling 858 megawatts in capacity with several more on the way. One of the bigger players is Innergex, a Quebec-based company with 11 operational run-of-river projects in B.C.

“B.C. has all the elements you need in the equation for run-of-river. You benefit from Costal Mountains with a very high head, you have tons of creeks, huge accumulations of rain and snow, which provides the flow you need. It’s the perfect topography, perfect climate, and there is huge potential in British Columbia,” says Richard Blanchet, senior vice president for Innergex.

The big difference between these projects and the massive hydroelectric projects of old is scale and the lack of water storage. In conventional hydro projects vast tracts of land are flooded in order to accommodate water storage. Run-of-river the projects are at the mercy of the flow of river, this means more variability in the electricity output, but fewer environmental impacts.

In the winter output drops and a project like Fitzsimmons Creek can even be shut down for periods of time, as it was when we were there. It’s in the spring when the melt in on that these projects make their money.

Environmental impacts

The view down Fitzsimmons Creek from just below the weir that is part of the Innergex run-of-river project nestled between Whistler Mountain and Blackcomb Peak. Photo David Dodge

Compared to a large hydro dam the impacts tend to be much lower, and these projects produce nearly no greenhouse gas emissions, but no type of energy development is without impacts.

Perhaps the biggest factor is that run-of-river projects are typically constructed in remote, mountainous, and ecologically diverse areas.

A small dam called a headpond is created at the top of the stream in question. This is where water is diverted into a pipe called a penstock. That pipe then travels down hill several kilometers to the powerhouse. In the business this area between the headpond and the powerhouse is called the diversion reach and is the area where the most hydrologic effects are felt.

Access roads have to be cut to the headpond and the powerhouse and you have to get the power out of there with transmission lines.

At Fitzsimmons Creek the power is needed locally and the transmission infrastructure was buried on already disturbed land.

While some water is diverted to generate power, it is key is to always maintain a flow rate in the stream that never drops below a minimum level in order to protect the ecological health of the creek and the fish and other species in it. (To see the environmental mitigations that took place at Fitzsimmons Creek click here).

Monitoring is required to ensure this happens. A report in January from the Globe and Mail found over 700 water-use and reporting violations at 16 B.C. run-of-river facilities in 2010 alone. This information came to a light after a government audit was accessed through a Freedom of Information request by the Globe and Mail newspaper.

“Just under half of the 749 violations dealt with improper water use, including increasing or decreasing water flow too quickly – also known as “ramping” – which can strand or kill fish,” says the report.

The Fitzsimmons Creek facility had 25 violations in 2010, the fifth highest. Bas Brusche, the director of public affairs for Innergex was quoted in the report saying there were only three violations in 2012 and one was due to lightning.

“We have started a fish-monitoring program [and] we have spent now about $230,000,” Brusche was quoted as saying.

Run-of-river positives and negatives

This isn’t to say that run-of-river hydro is bad, but it is important to discuss its impacts. Run-of-river projects can offer tremendous positives when compared to almost any other form of electricity generation.

It emits nearly no carbon, no mercury and no particulate matter, and because water is dense can produce a lot of energy for a relatively small environmental disturbance. In a comparison of several common electricity generation technologies by the Ontario Power Authority run-of-river was found to have the lowest environmental impact by far.

Run-of-river projects have also been developed in remote First Nations communities. Developers get a profitable run-of-river project and remote First Nations like the Douglas First Nation get reliable electricity and the economic development opportunities that come with it. Located on the north end of Harrison Lake it’s about 65 kilometers from Vancouver in a straight line but about 6.5 hours by a frequently washed out logging road. When you consider that that road was the only way in for their previous energy source, diesel was trucked in for generators, run-of-river looks pretty good by comparison.

Planning and construction is happening on 67 more run-of-river projects in the province of B.C. While the government of B.C. faces protests over its controversial Site C project, a massive hydro dam in the Peace river area, run-of-river offers a human scale, lower impact solution.