By David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

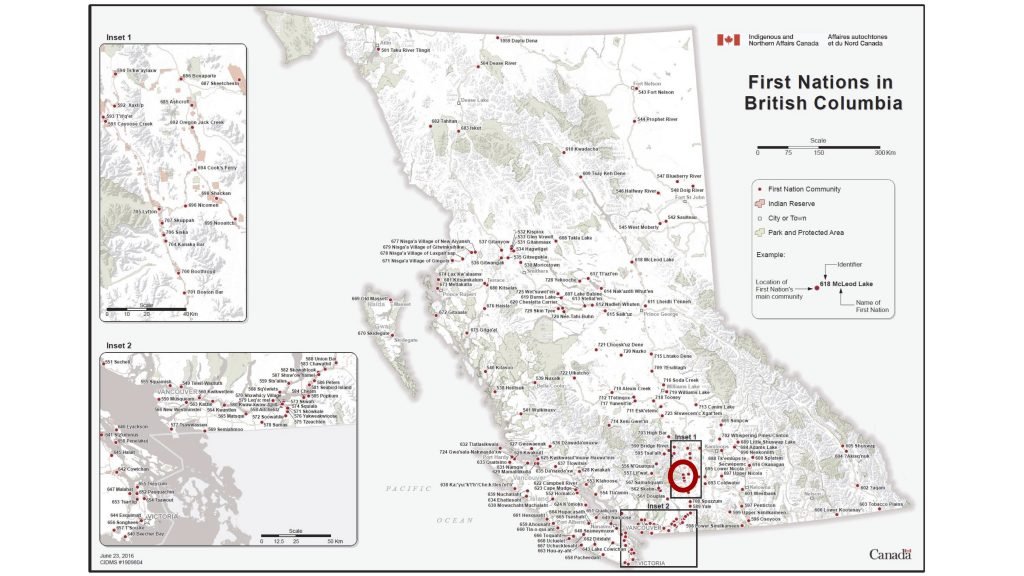

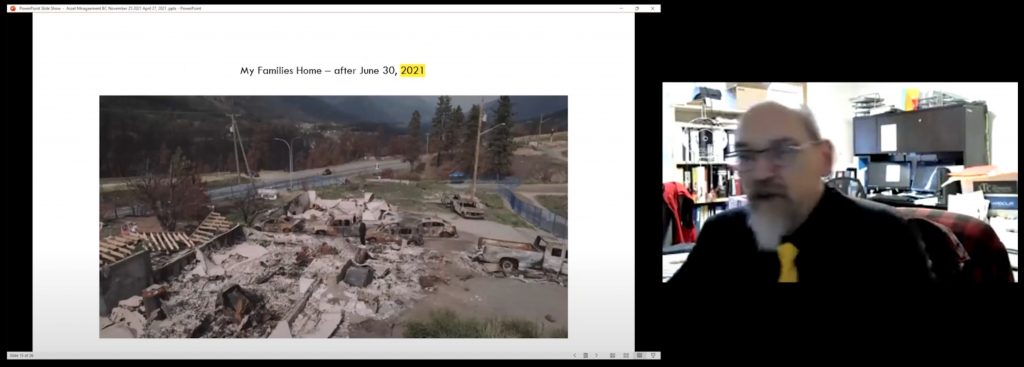

Chief Patrick Michell of the Kanaka Bar Indian Band lost his home in Lytton, a town of 1,200 people in the south-central region of the province. Kanaka Bar is part of the Nlaka’pamux First Nation and is located just 15 kilometers south of Lytton.

On that day, Lytton became the poster child of climate change-induced severe weather calamities.

Lytton set a new Canadian record temperature of 49.6 degrees Celsius, under the so-called “heat dome” that locked western Canada in a severe heatwave.

“The very first person who reported the fire was at 4:38 pm on June 30th,” says Chief Michell. “By 5 o’clock my home was on fire” almost two kilometers away from the origin of the fire.

“Then the fire just traveled like a snake or a dragon from home to home, to home, to home. Nothing could stop it. Because we didn’t design our urban layout for this type of weather.”

In short order, 90 per cent of the town was leveled.

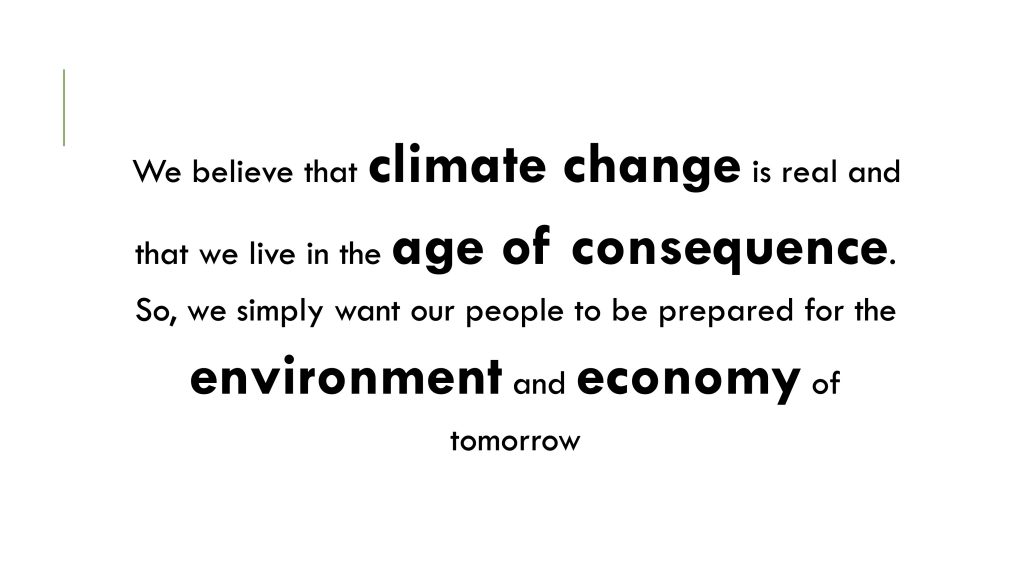

“Climate change is now producing the extreme weather events, the heat dome, the atmospheric river, the extreme cold, and of course, wind events,” says Michell. “So here we are caught in this vicious climate change cycle.”

Before 2021 was over, rare November floods hit Lytton and Kanaka Bar, washing out highways. Then, in December Kanaka Bar experienced extremely cold temperatures of -26 Celsius and delivered four feet of snow.

According to the Insurance Bureau of Canada, 2021’s severe weather resulted in $2.1 billion in payouts in Canada alone. But the biggest payouts in Canadian history are the Fort McMurray fire of 2016 at $5.4 billion, the Alberta and Ontario floods of 2013 at $3.5 billion, and the 1998 Quebec ice storm at $2.5 billion.

So, have we learned anything?

That’s debatable since, in the aftermath of these disasters, funds are in short supply. There is a panic to rebuild fast and we often rebuild the same old thing that was decimated in previous disasters.

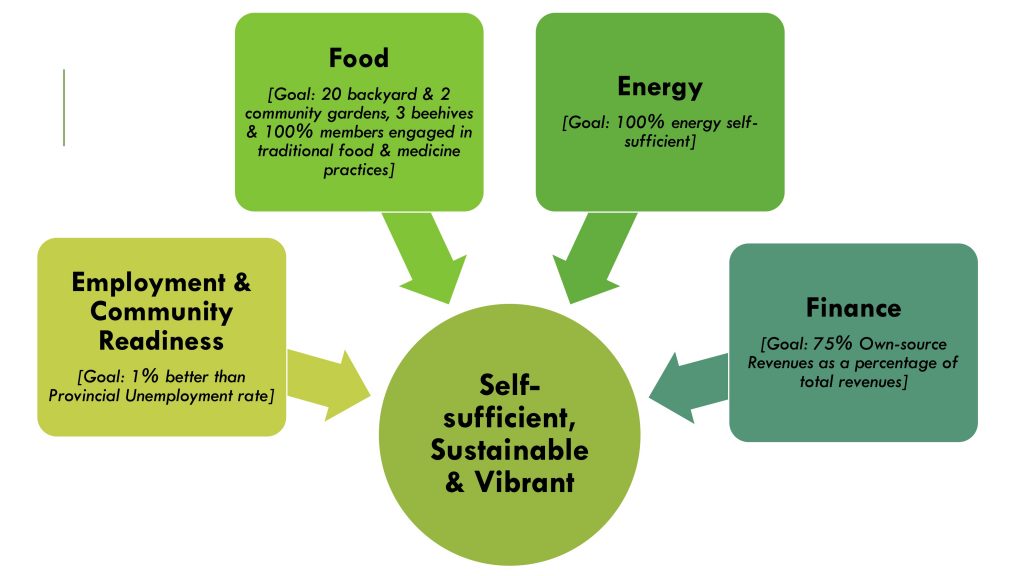

This was on Chief Patrick Michell’s mind for years before the Lytton fires. The Kanaka Bar band has done tons of research into climate impacts and currently has a plan to build a climate-resilient community that includes secure energy, homes, and even food supply security.

“Since 1988, we’ve been warning the federal and provincial governments about cumulative effects and the climate change and the extreme weather events,” says Chief Michell.

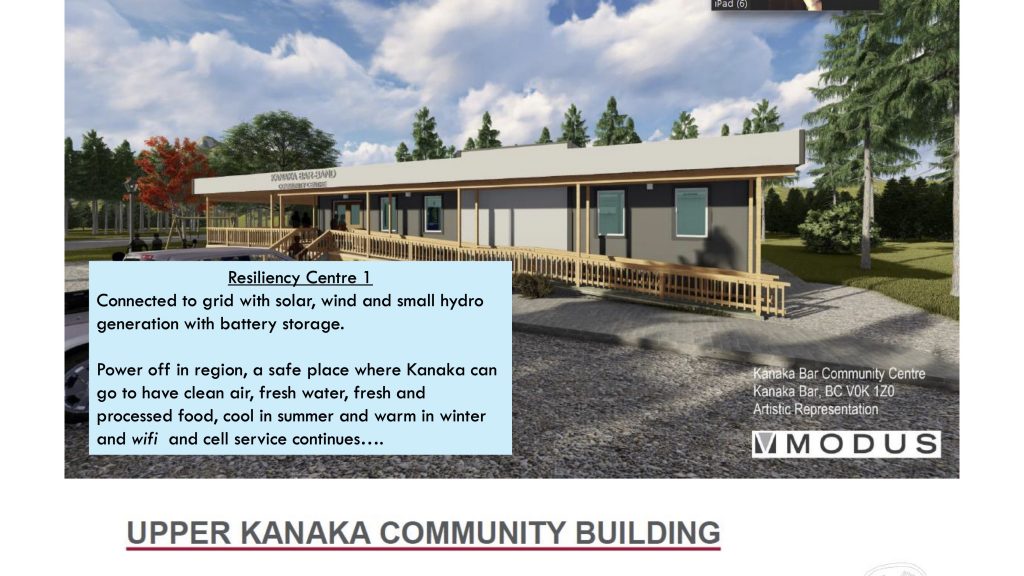

The band has built a community building powered by solar with 36 hours of battery storage so it will keep operating if the grid goes down.

In 2013, they built the Kwoiek Creek 50 megawatt run-of-river power project, in partnership with Innergex Renewable Energy, as part of their plan to achieve energy, employment, and financial resilience.

Living in straw homes

The trouble today is “We live in buildings that were designed for the weather of yesterday.” It didn’t matter whether the homes had stucco, aluminum, hardboard, or vinyl siding, they all burned to the ground in the fire.

Chief Michell invokes the story of the three little pigs to make his point. The wolf blows down the straw and sticks homes, but “The Wolf fails on brick.”

Chief Michell isn’t sure what the best material is to guard against wildfires and extreme weather, but he’s pretty sure it has some brick-like qualities. (A brick wall can achieve a one-to-four-hour fire-resistance rating).

Melanie Ross is with SAIT’s Green Buildings Technologies (GBT) research group in Calgary. When they saw the fires ravage Lytton in 2021 “We thought immediately that we could go in and help.”

Chief Michell thought this was a good idea “So SAIT is working together with us and Melanie Ross and her team of up to 14 people are scouring the world for solutions.”

SAIT has engaged Foresight Canada to issue a call for the best climate resilience building solutions for Lytton and Kanaka Bar.

Building back right means no emissions and climate resilient homes

And this time, both Chief Michell and SAIT want to build back right. “We want to get to a point where we have a zero-carbon emissions home with highly resilient materials that allow people to withstand major climate events and be able to pick up the pieces and continue to live,” says Ross.

Kanaka Bar had a housing development in the works before the fires and now that’s moving forward in earnest with the assistance of SAIT’s GBT.

SAIT will recommend several building solutions that are best for building homes resilient to severe weather events and fires that also do not produce emissions to feed climate change even more.

“We’re going to build four duplexes to create eight units of residential housing and it’s going to be affordable,” says Ross.

Then SAIT will continue to monitor the housing and use what they learn in future recommendations to other builders and municipalities.

We have a small window to get climate resiliency right

Chief Michell says there is far too much energy going into protecting the status quo while the climate emergency is already ravaging communities.

“So, we have this small window left,” he says the consequences of putting off investments in resiliency are very significant: “Our transportation systems are gone; our communications systems are gone, our wastewater systems are gone and our energy systems are gone,” says Michell.

“Our heart breaks for anybody who’s experiencing the emergency response to an extreme weather event. The fleeing, the evacuation, the psychological and emotional trauma that they’re going through to land in a town and to be chased away from that town.”

“When the fire gets to that town and then a goddamn flood wipes out the bridge and you’re getting layers and layers of trauma. British Columbians and Canadians are running from event to event to event. And yet if we invest today, we can shelter in place, immune from the extreme weather events of the future.”