By David Dodge and Kay Rollans

“Just look around us. I mean, this is the commute daily on an e-bike.” Leon Milner gestures to Edmonton’s beautiful Saskatchewan River Valley as he rides his e-bike on his commute from his home on the southside to his downtown office.

Leon’s commute is only about 15 or 20 minutes, “which is way faster than the bus or a car during rush hour,” he says with a smile.

Leon no longer has a car. He swapped a drive down some of Edmonton’s busiest streets for a ride on river valley trails and downtown bike lanes. He’s given to waxing poetic about the ride. “You hear the birds in the morning and see squirrels,” he says. “It’s such a treat to take advantage of Edmonton’s amazing river valley.”

E-bike sales began taking off around the world prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in Europe where the climate change plans of certain cities and countries favour active transportation like cycling because of their tremendous emissions reduction benefits.

Cities like Copenhagen already boast bicycle modal share rates of 49 per cent — that is, 49 per cent of all trips in the city are currently made by bicycle. Their plan is ultimately to have 75 percent of all trips conducted by some form of active or public transit. Vancouver has a similar goal: 66 per cent of all trips to be active or by transit by 2025.

For Leon, the decision to drop his car was made pragmatically by analyzing the cost of owning a car versus owning a bike. Since he already lives in the core of the city, numerous alternative modes of transportation are feasible — all the more so because, by eliminating the car, he saves about $7,000 per year, including $350 per month in parking.

“Just being able to park in the heated underground parkade for free at work, and driving right up to your meetings, going straight up the elevator, not having to deal with parking, congestion, noise, anything. I mean, it’s pretty great,” says Leon.

Distances melt away with e-bike

Distances just seem to “melt away,” says Leon. “I think it’s just effortless. I think that’s the thing I like the most … I can use it as a legitimate form of transportation in place of a car for getting to work, for buying groceries, for visiting with friends, just for having fun on it as well. And it’s just a blast to ride.”

I, too, began riding an e-bike just over a year ago after being totally smitten by a story we did on e-bikes a few years ago. My own commute is 10 km from the suburbs of Edmonton – one of the most sprawling cities in the world. Like Leon, my e-bike gets me downtown in about the same time as a car, and I can attest that the ride is much more pleasant than the drive.

One of the most transformative things that the e-bike does is to remove many of the psychological barriers to cycling — barriers that, as the name suggests, are mostly in our heads. “The wind is blowing today” or “I’m too tired today” or “I don’t have time to ride” are just a few of the refrains that seem to “melt away” along with the distance.

Another one of those refrains? “It’s too cold out.” For Leon, who made the decision to ride year-round in the most northerly city of its size in the western hemisphere, the e-bike removes this barrier as well. “One of the key advantages and reasons for me getting this bike is because I can ride in the winter. I put studded tires on it and the tires are huge.”

Leon’s bike has both a throttle and a multi-level pedal assist. Other models, like my own, have only pedal assist. It doesn’t take long to learn that the e-bike is more than adequate to get you where you’re going. For most people, riding at 32 kilometers per hour on a regular bike (the maximum speed e-bikes are allowed to run in Canada) for any length of time is not possible. I have only encountered a couple of cyclists who are able to consistently maintain such a high speed.

On an e-bike, once you reach maximum speed, the pedal-assist drops out. It feels like the bike is putting on the brakes. It’s not unpleasant, but you nonetheless learn quickly and intuitively to manage your own speed at around 30 kilometers per hour.

The e-bike revolution

Electric vehicle columnist Matthew Klippenstein thinks the e-bike is the revolution in active transportation. Since COVID-19 hit, e-bike sales in Germany have skyrocketed 226 per cent. There are also impressive numbers out of the United States: US e-bike company Electrek’s sales are up 140 per cent since March, and Seattle-based Rad Power Bikes says its sales in April were up 297 per cent.

In recent years, Copenhagen over-took Amsterdam as the most bicycle friendly city in the world. In Canada, Vancouver and Montreal are leading the way — the only Canadian cities to crack the top 20 cities for bicycle use globally.

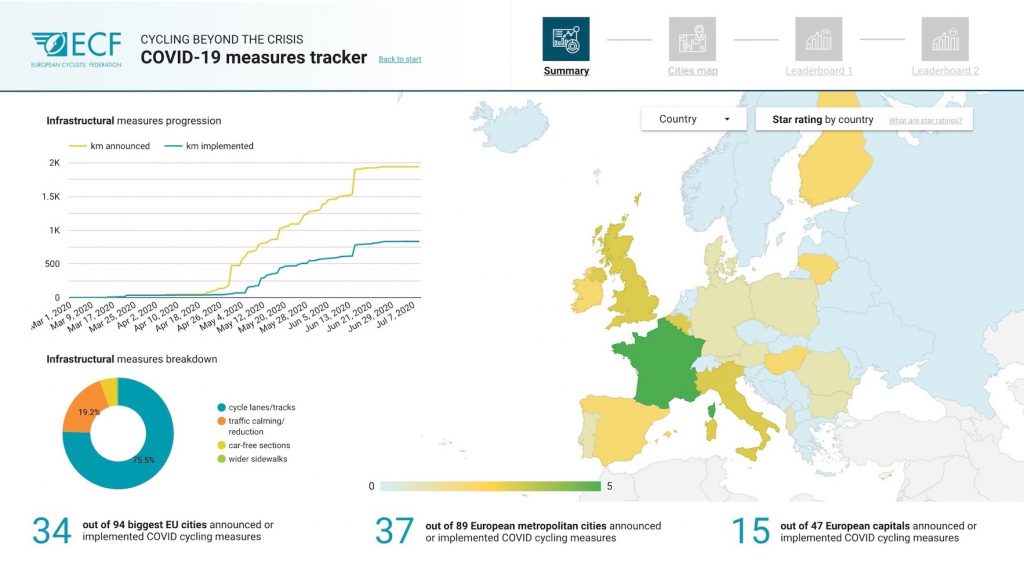

In Europe, 34 cities have launched aggressive cycling strategies as a response to COVID-19, pledging to build 750 km of new bike lanes, offer incentives, and pursue other strategies to make the choice to ditch the car an easier one.

Taking into account the ways in which cycling relieves stress on public infrastructure by contributing positively to climate, environment, health, and other areas, the European Cycling Federation estimates the economic value of cycling to be about $240 billion.

This is why mode shift and cycling in particular are such prominent features in City climate change plans. It cost very little to encourage and support cyclists and the emissions reductions are significant.

Clearly, there’s a huge demand for e-bikes, but in many places, there are a few more hurdles to overcome. The automobile has created disconnected, massive, sprawling cities largely unfriendly to pedestrians and cyclists.

Klippenstein says one of the benefits of increased bike sales is that cyclists are becoming a constituency with political clout. As support for bicycles increases, it will become increasingly easier for cities to invest in bicycle infrastructure.

Millennials opting for more urban lifestyles that don’t require cars, they have greater consciousness around climate change, and with urban and national emissions reductions plans around the world that favour mode shift to active transportation, our cities are being transformed. After years of building expensive car-driven infrastructure, we’re seeing a steady shift towards people-centred design.

What comes first: the e-bike or the infrastructure?

Personally, I used to scoff at people who cited safety as a reason not to cycle. After riding through my first winter, my mind has totally changed.

“I would never have started cycling without the bike lanes, without having protected bike lanes on the way to work. I just feel totally unsafe,” says Leon. Infrastructure is absolutely essential to cities if they want to encourage year-round cycling not just in hard-core cyclists, but for average bicycle users. This is especially true in winter cities like Edmonton.

Edmonton’s new City Plan calls for 50 per cent of trips to be made by transit, cycling, or walking in support of its Energy Transition Strategy. This would be a big shift from its present rate of 23 per cent.

So far, many of the really transformational changes are yet to be delivered. To its credit, the city did release an e-bike incentive program in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. The program was designed to get people excited about e-bikes, support mode shift, and transform the market. Ultimately, however, local politicians got weak knees and shelved it for a few years.

Still, during the few weeks the incentive was available retailers reported bike sales soared.

There is no question there is a little snobbery from conventional cyclists. Both Leon and I have heard that e-bikes are the “lazy” form of cycling, but this perspective doesn’t look at the big picture. Klippenstein and Leon both agree the e-bike has the potential to transform cycling as a valid and accessible form of transportation, making it a viable choice for older riders, people with longer commutes, and people whose commitment to cycling is diminished by simple barriers.

As for being a lazy e-biker my response is this: Yes, riding an e-bike takes half the effort, but I ride four times more often. Who can scoff at that?