By David Dodge and Duncan Kinney

Nothing makes you appreciate the power of the ocean more than coming within a whisker of getting tossed into it with a load of camera gear. We were on a zodiac on the Bay of Fundy conducting an interview with Matt Lumley, the communications coordinator for the Fundy Ocean Research Centre for Energy or FORCE, and in the middle of one heck of a spring tide.

In fact, it was one of the highest spring tides of recent memory. Of course, this all had to be explained in some detail to a land-bound Albertan like me. But it turns out then when the Sun, Moon, and the Earth align (called a syzygy) you get a powerful tide. While Lumley held tight to the gunnels of the zodiac, I hit the deck hard. I was grateful to not have ended up in the water but my digital SLR was a useless brick for the rest of the trip.

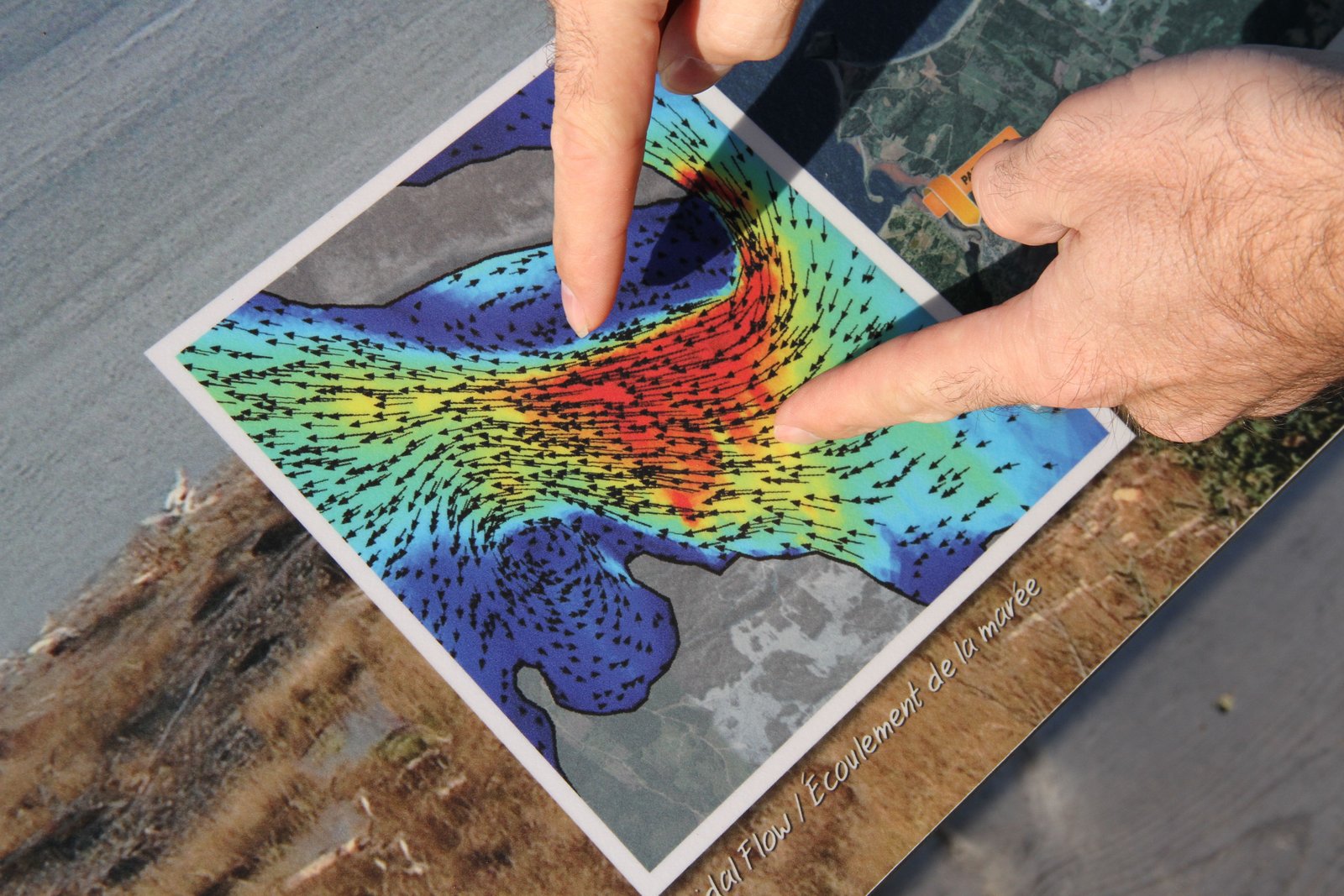

On an average day about 160 billion tonnes of seawater flows into the Bay of Fundy. That’s more than four times the combined flow of all of the freshwater rivers in the world. We were in the Minas Passage, an area of the Bay of Fundy where the seafloor and the shoreline pinch together. Here, the water goes from moving at about one meter a second to five. It’s like putting your thumb over the garden hose and getting that extra-powerful stream. This is where FORCE decided to put their tidal energy test site.

The churning water at Black Rock with Split Rock visible in the background on the Bay of Fundy – here the tide can rise 14 metres and race along at five metres per second. The Fundy Ocean Research Centre for Energy is testing three to four different in-stream tidal technologies at their grid-connected test site in the Minas Passage. Photo David Dodge

EXTRAORDINARY POTENTIAL BUT STILL EARLY STAGES

According to recent models Lumley says there is roughly 7,000 megawatts of potentially extractable tidal energy in the Minas Basin. Of that number, researchers say about 2,500 megawatts can be tapped safely. That’s more than enough electricity for all of Nova Scotia.

Matthew Lumley from the Fundy Ocean Research Centre for Energy says 160 billion tons of water moves in and out of the Bay of Funday everyday making this one of the best places to generate tidal electricity on Earth. Photo David Dodge

Indeed this enormous storehouse of energy is the reason why the province and Premier Darrell Dexter created the Fundy Ocean Research Center on Energy. There are two objectives for the centre.

“One, try to figure out how we can extract some of that energy out of the Bay of Fundy and two how we can develop good tidal technology that we can then hopefully sell to the world,” says Dexter.

FORCE may only be deploying up to a maximum of five megawatts of test projects for now but there is no shortage of ambition. Subsea cables already in place have a capacity for 64 megawatts of grid-connected projects. There is also a nearby substation and a connection to the larger power grid that developers can take advantage of.

The first pilot project was installed by Nova Scotia Power at FORCE’s test site, it has already concluded and several more are in the works.

Planning for success, Nova Scotia is creating a special commercial-scale tidal feed-in tariff that is under development. It’s only for projects that are 500 kilowatts and above. This is a companion to the province’s community feed-in tariff (COMFIT) program that we recently wrote about which also has a special rate for tidal projects.

A company called Fundy Tidal has five small-scale tidal projects that have been approved by the COMFIT program and are currently in development. Here’s a map showing where they are.

OLD AND NEW TIDAL ENERGY TECHNOLOGY

The 20-megawatt tidal energy generating station at Annapolis is one of a kind in North America. Although the idea works, the idea of making barrages of dams across inlets in the ocean has lost favour due to high environmental impacts. Instream tidal energy technologies are being tested now. Photo David Dodge

Nova Scotia is home to one of only a few operating tidal barrage power plants in the world. The Annapolis Tidal Station is a 20-megawatt system that came online in 1984. It’s a tidal barrage system and it operates much like a traditional hydroelectric station. You build a large dam over a tidal inflow and then capture the tide as it floods in. As the ebb tide begins the water is released from the dam through a turbine. Much like large hydro plants though, the environmental effects can be significant.

There are shoreline and sedimentation effects that drastically change the area around these tidal generating stations and as a result, they’re not really being built anymore.

What is in vogue is what’s called in-stream tidal. Lumley likens it to an underwater wind turbine that sits on the seafloor. These in-stream generators take advantage of the water going both ways. John Woods is with Minas Pulp and Power. It’s developing a tidal turbine project at FORCE that’s slated to go in the water in 2015-2016.

The actual power output of a well-sited wind farm is about 35 per cent compared to its full nameplate capacity. If it was a 100-megawatt wind farm it’s usually only effectively producing 35 megawatts over a given period of time. This is called capacity factor.

The tidal technology that Woods’ company is interested in has a 70 to 80 per cent capacity factor.

“These things are moving all the time, whether the tide is in the flood condition or the ebb. They’re moving both ways because they’re bidirectional,” says Woods.

CHALLENGES

Of course, there’s a reason we’re talking about projects in 2016 and about all of the research and development that’s being done at FORCE instead of finished projects. Developing commercial-scale tidal technology has proven to be immensely difficult. The ocean is a difficult place to make a living, just ask a fisher, and it doesn’t get any easier for tidal energy developers. Especially when they’ve chosen the place with some of the most powerful tides on earth.

While Woods and his company were very happy to get the contract and the chance to develop a tidal project at FORCE, Woods likens it to a dog chasing a car. What happens when the dog latches onto the bumper?

In 2010, Irish company OpenHydro, in partnership with Nova Scotia Power, put a one-megawatt turbine into the water at FORCE’s test site. It lasted about three weeks surviving only two spring tides before the turbine blades were destroyed.

It turns out that the resource was far more powerful than anyone had expected. In fact, that one-megawatt turbine was putting out two and a half megawatts worth of energy before it spun itself to pieces. Still, it’s not all bad news. Doug Keefe of FORCE offered a bit of perspective in the CBC story.

“It’s like they broke a drill bit, but they discovered that we have a reservoir that’s twice as big as anyone thought.”

Alstom, Atlantis and Minas Basin Pulp and Power are each teed up to install tidal technologies at berths at the Fund Ocean Research Centre for Energy’s site in the Bay of Fundy.

OIL SANDS ANALOGY

Matthew Lumley shows a figure that illustrates how the coastline pinches in Minas Passage to produce a flood tide that races along more like a river than a tide. Photo David Dodge

“In a way, it’s similar to the tar sands because we’ve known for a long time we have this enormous power resource,” says Lumley. “The question is can we come up with the technology that makes it viable, both economically and environmentally to extract it, and we’re not there yet, but when you look at the out at the Bay of Fundy you know you’ve got a resource.”

The current tidal industry does bear a striking similarity to the oilsands industry of the 80s and 90s. Back then it was a money loser and government and industry slowly worked together to commercialize the technology and extract the resource in a profitable way.

It must be frustrating to know that out there, just out of your fingertips, is a massive store of energy, wealth, jobs, and profits. The government of Nova Scotia is certainly intrigued by the potential of tidal power. All that’s left is a developer that puts it all together in the Bay of Fundy, the Mount Everest of tidal energy resources.