By David Dodge and Duncan Kinney

You hike over the crest of the hill and there it is: 96 sun-tracking solar masts, each with 42 solar modules — 4,032 modules in all — perched on the side of a hill with the beautiful Rocky Mountains in the background.

It’s called the SunMine project and it’s all part of the reinvention of Kimberley, B.C., from mining town to a clean tech, tourism town of the future.

Kimberley, population 6,700, was founded in 1917 to serve the Sullivan mine, the largest lead-zinc mine in the world. The Sullivan mine was closed in 2001, mined out after more than 100 years of operation. More than $20 billion worth of lead, zinc and silver came from that mine, but what’s left today is 1,000 hectares of contaminated brownfield right in the city with little chance of any productive, tax-generating use.

This is what inspired solar advocates and local politicians to try mining the sun on the old mine site.

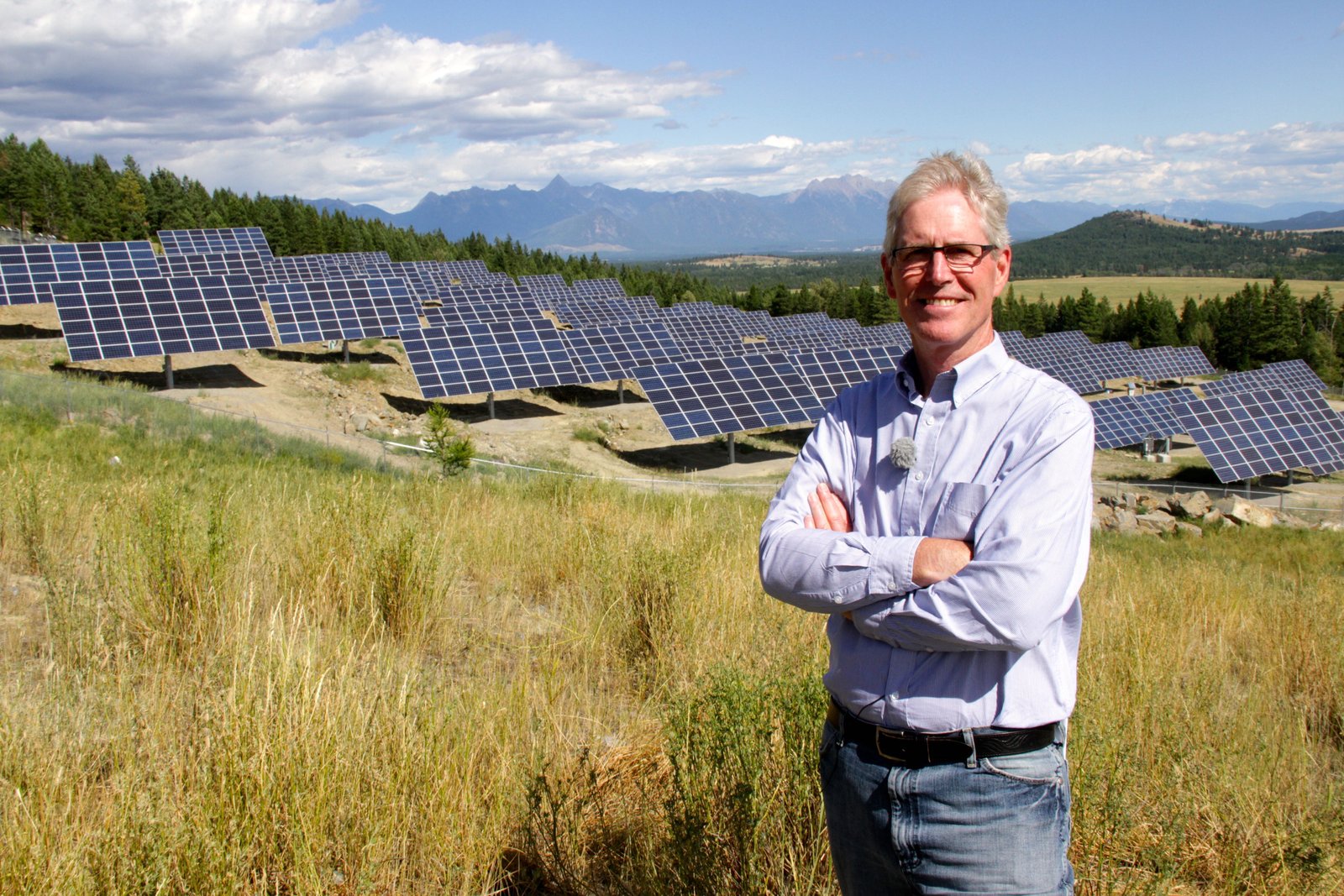

The former mine land “can’t really be used for anything without some radical environmental remediation, so when the opportunity for the SunMine came up it just seemed like a natural thing to do. Kind of a rebirth of the brownfield into something useful,” says Mayor Don McCormick as he stands on the hill over looking the solar project.

Kimberley Mayor Don McCormick at the mountain city’s large sun tracking 1-megawatt solar farm a project designed to re-brand Kimberley as a modern, clean energy tourism town. Photo David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

Kimberley has an excellent solar resource, a lot of land that wasn’t doing anything, and all of the transmission infrastructure that once served the mine. SunMine is a 1.05-megawatt solar tracking PV project that started producing power and revenue of $1,000/day in June of 2015. The five-hectare site at the former Sullivan mine is leased from owner company Teck.

The SunMine project was developed by Michel de Spot of Vancouver’s Ecosmart Foundation working with former Mayor Jim Ogilvie. Kimberley built SunMine with the support of its citizens. In 2011 a 76 per cent majority of voters supported borrowing $2 million dollars for the project. For a town of 6,700 people, taking out that kind of loan is no small undertaking.

The project is the first large-scale solar project in western Canada to use tracking technology. Each solar tracking mast supports 42 solar modules in the shape of a rectangle. The dual trackers follow the sun, optimizing the angle of the array in order to maximize sun exposure and power output.

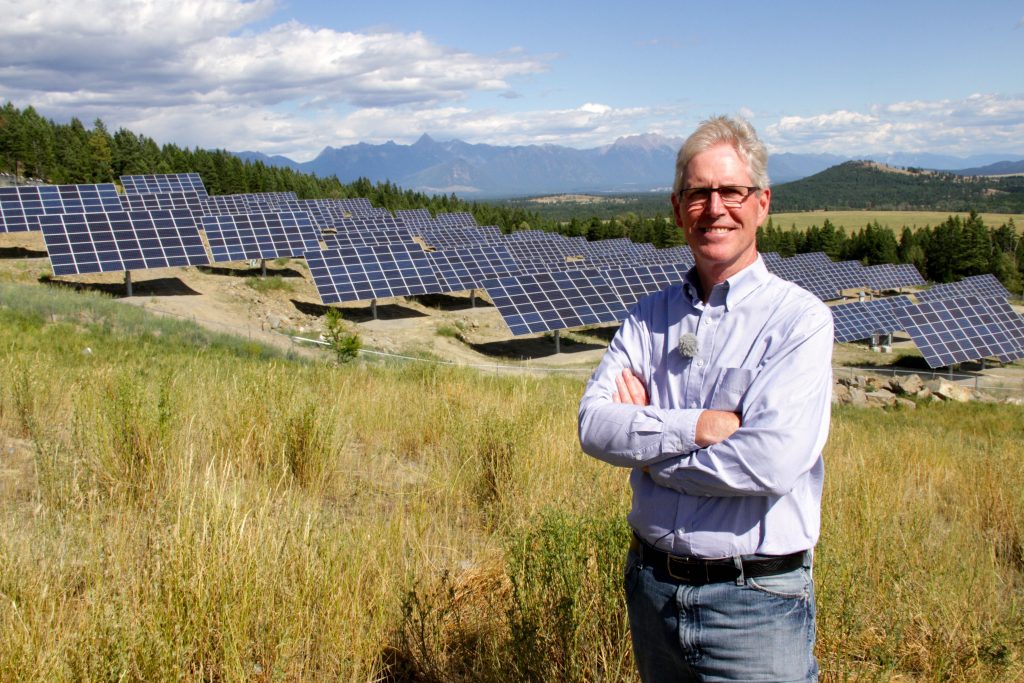

Kimberley economic development officer Kevin Wilson explains there is room for up to 200 megawatts more solar on the former mine site. Photo David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

“The tracking system allows us to increase production earlier in the day and later in the day, to round out the corners of the production curve,” says Kevin Wilson, the economic development officer for Kimberley. “It also happens to be that earlier in the day and later in the day are the points of time where BC Hydro pays a premium for energy during the periods of highest demand.”

According to Wilson, the trackers help the project generate 40 per cent more electricity than a standard fixed solar project. The system was not cheap, costing $5.4 million. The new technology, site conditions, scale and usual first-time project management headaches combined to drive up the price. On top of the city’s loan for $2 million, Teck contributed about $2 million, B.C. innovation funding another million, and the Southern Interior Initiative Trust the final $400,000.

Incredibly there is enough brownfield land and transmission capacity in the area for a further 200 megawatts of solar. Both Wilson and McCormick mentioned the possibility of future projects.

After losing 600 mining jobs with the closure of the Sullivan Mine in 2001 Kimberley B.C. has been been on a journey to re-brand the City as a mountain tourism town with golfing, skiing and people friendly streets. Photo David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

“I think the coolest thing is the opportunity for us to present Kimberley in a completely different light to the world,” says McCormick. “It’s a rebranding of the community, and it’s an opportunity to do something cool and innovative simply beyond tourism.”

“We have an alpine ski hill that’s got about 85 runs right within the city limits. We have three championship golf courses, again within our city limits, and in fact we like to say that we have more golf courses then we do traffic lights in town, and this is pretty good for people wanting to visit the community,” says McCormick.

Kimberley lost 600 jobs and 1,600 residents after the closure of the mine. It’s a long and winding road, but population numbers are back up to 6,700 and new jobs are slowly being created. And McCormick and his council have ideas for attracting new industries to build on the clean tech angle.

While this first-of-its-kind solar project might have been expensive, it’s pointing the way to using brownfield land for clean energy production. These types of projects come with their own learning curves, but Canada has no shortage of brownfield space that could be converted to solar farms. According to the Federation of Canadian Municpalities up to 25 per cent of Canada’s urban land is contaminated by previous industrial activities.

Solar has certainly changed the view of the brownfield in Kimberley, and it seems like a no-brainer as a solution for brownfields all across this country.