By David Dodge

Currently, the biggest barrier to people and organizations investing in energy-efficiency upgrades and renewable energy on their buildings is access to affordable financing.

That’s according to Brian Scott, an Edmonton developer and Leigh Bond, an entrepreneur who has been working on geothermal and energy efficiency projects for the past decade.

That’s why they are both advocating for bringing PACE financing to Alberta.

“Back in 2009, in Berkeley, California, a concept was hatched called PACE, it stands for Property Assessed Clean Energy. And it’s a financing program which has taken some parts of the U.S. by storm, and it allows people to get 100 per cent financing upfront to upgrade their buildings, and repay the financing over time out of the savings. It’s a game changer,” says Scott.

Finance things that save more money than they cost

Funding energy efficiency upgrades with PACE means the upgrades are assessed against the property and not the owner. Photo David Dodge

What kinds of things are we talking about financing?

“Basically any upgrade that is more energy efficient than what it’s replacing, and that can be as fancy as a new solar system, or it can be as simple as a new high energy-efficient furnace at 96 per cent,” says Leigh Bond. “It can be windows, it can be insulation, it can be anything that makes the property more energy efficient.”

Here’s the problem PACE solves: I want to install a solar system. I know it will pay for itself, but it could take 15-18 years. My solar modules are guaranteed for 25 years, but banks are twitchy about long-term loans. Finally, what happens if I sell my house?

“It’s not a loan,” says Bond. “It’s financing. It’s a way of buying something that generates revenue, and then being able to pay that financing back over time, over the life of the product.”

In effect the money is paid back out of the energy savings and over relatively long terms.

“It’s attached to the property, instead of to the person. The person living in the house gets the benefit, the lower energy bill, but at the same time, they also get the cost. When it gets transferred to the new owner, they get both the savings in energy and has to pay for the cost.”

It’s similar to a local improvement charge for something like paving your alley.

PACE has created $3.4 billion in projects

And the idea seems to work. In the U.S., “PACE financing for single family homes, has been $3.4 billion, generating about $6 billion of economic activity. In the commercial sector, it’s been $340 million,” says Scott.

Not all PACE programs have been successful. It matters how the program is set up and how you execute it, explains Bond. He says a good Alberta-based program should replicate successes in the U.S.

“The first thing is to call it PACE… if you don’t call it PACE, then you’re on an uphill battle to market the concept,” says Bond. Then he recommends setting up an independent organization to run the program. A “non-profit or co-op” would be his choice. The third thing you need is access to plenty of capital. Although it can be public money, Bond says it’s more likely to be private capital.

Then there are risk-adverse banks who worry PACE debt will get in front of their mortgages.

But Scott says this can be managed in a couple of ways. He says the value of the property goes up by more than the investment in the PACE financing, which means their security is even better than it was to begin with.

Scott says upon foreclosure PACE debt does not need to be fully paid out, it’s just the current obligations that need to be covered.

Who cares about PACE?

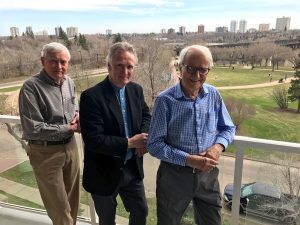

Brian Scott, developer, Leigh Bond renewable energy contractor and John Halun, resident of the Grandin Green housing cooperative. Scott accessed green financing 20 years ago to building super energy efficient features into the apartment building cooperative. He’d like to see PACE financing brought to Alberta to stimulate investment in energy efficiency and renewable energy in new and old buildings. Photo David Dodge

“Basically, everybody’s interested,” says Bond. “Contractors, in particular, of course, because they’ll increase their revenue; Municipalities, because they don’t have to put up the money; Lenders of big financial companies are willing to come into Alberta with billions of dollars. And like I said, at the municipal level, the City of Edmonton, in fact, sent Brian and I to do a research project at the PACE Summit in Denver in February.”

Leigh Bond has been one of those contractors: “In 12 years we’ve done 110 projects. But I could have done 1,000 if I had PACE financing because people want to do this, but that front end cost is a barrier.”

Brian Scott’s firm is Communitas and his first experience with green financing occurred 20-years ago with his Grandin Green condo co-op project in downtown Edmonton.

“Grandin Green ended up looking for green financing and they upgraded the building here to the tune of $1.3 million dollars,” says Scott. “But they had to go out of province to get that money. PACE financing is the solution to this.”

The City of Edmonton is pursuing PACE as part of its energy transition strategy, but it seems others are interested as well.

“The Town of Devon wants to be a net-zero community,” says Scott. “They see PACE as being a perfect instrument for getting there. Drayton Valley is interested in this. The City of Red Deer has already passed a by-law or a resolution to adopt the PACE program. Brazeau County, and even Wabasca recently contacted us and said they’re super interested.”

“The bottom line is PACE financing could seriously reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas production in buildings by anywhere from 50 to 80 per cent,” says Scott. “In fact, we could even get to net-zero.”