By David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

Twenty years ago, Matthew Peneitz joined the Peace Corps and worked in Guatemala. The poverty he saw changed his life, and in time, that of many others.

“I’d never seen anything like that before. And I think the paramedic in me took over, and I wanted to rescue as many people as I possibly could who were living in extremely impoverished conditions,” says Peneitz.

“And so, after my Peace Corps service, I decided to start an NGO so I could keep doing the work that I had started. And that was the birth of Long Way Home.”

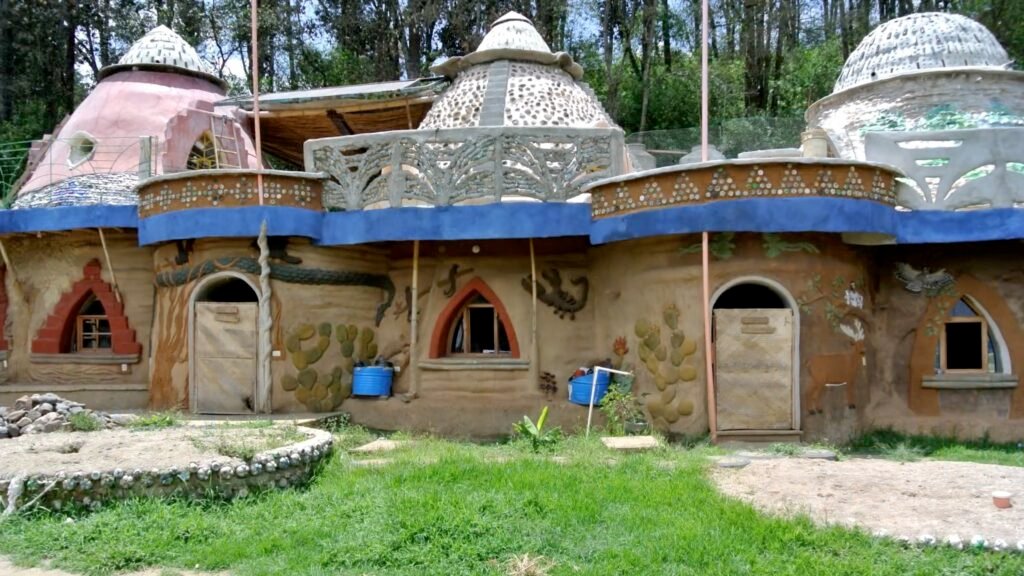

It’s an inspiring story. Matthew and Long Way Home built a park and a school campus, and have undertaken hundreds of community projects over the last 20 years. And remarkably, they build using tires, soil and trash.

For Matthew, the journey began soon after his service in the Peace Corps.

“I did it from scratch. I raffled my 1973 Caprice Classic convertible to get some money to get started and then bought a $500 Volkswagen Jetta.”

“I drove all the way from Oregon down to Guatemala. I picked up a couple of buddies in Texas along the way. And by February the first, we were building a city park in Comalapa,” says Matthew.

Matthew had worked as a carpenter and was a DIY kind of guy, so he had an idea of how to build things. And he was also very interested in sustainability broadly.

And although Compalapa is a long way home for Matthew, the name came from a Dwight Yoakum song on one of his favourite albums.

One person’s trash is another person’s treasure

The first thing he noticed was that there was no system of trash removal.

“Everybody throws their trash on the ground or burns it or throws it in the river. So we wanted to do something about that,” says Matthew.

Adam Howland, the cofounder of Long Way Home, asked him if he had ever heard of building out of trash.

“At that point, I’d never even heard of it. So, a friend of ours in the Peace Corps gave him a book, and that book was Earthship Volume One,” says Matthew.

Earthships and building out of trash

That book was written by Michael Reynolds, the rebel architect who pioneered the concept of building passive houses out of old tires and trash in the deserts of New Mexico.

It’s easy to see in everything they have built that these ideas shaped the whole future of Long Way Home.

“We followed the steps in the book to build the first structure out of tires,” says Matthew.

Everybody loved the idea.

“It’s weird that everybody would love it too, because what you’re doing is putting a tire on the ground. You’ve got a wheelbarrow of dirt. You’ve got a sledgehammer, and you’re beating dirt into the tires. And somehow everybody loves doing that,” says Matthew.

“And yeah, Earthship inspired the whole thing really.”

They soon found a suitable site with a south-facing hill.

People love pounding tires

“It took us three months to dig the platform out. We got volunteers, we hired some local builders, and said, ‘Hey, we’re going to build some classrooms out of tires.’”

After excavating soil from the middle of the platform, they started construction.

“We threw the tires in a row on the outside of the platform and then started tossing dirt into the tires and started using sledgehammers to pound those tires out. And after probably five, six months, we had our first set of buildings,” says Matthew.

“Then we decided to combine the use of tires with earth bags, and we built a building that was two stories high, with tires and earth bags on the bottom, and then trash bottles and cob on top in the form of a dome,” says Matthew.

“Everything is sort of roundish, because in Guatemala, there are a lot of earthquakes,” he says.

Matthew started the organization in 2004. They began building the school in 2009, so as Matthew says, “in a way, we’ve only done two projects.”

“But within those two projects, we’ve built 175, maybe 200 structures. Because the model of the school that we’re building is that we don’t want to be a regular school. We want to be a school that does green building, climate fighting, and poverty fighting all at the same time.”

The school was “a testing ground,” says Matthew. They built latrines using trash bottles and framed it out of bamboo.

Earthship 2.0

“We have been combining trash with conventional materials on our campus for 17 years and have done a whole variety of buildings,” he says.

As Matthew quickly learned, building a school was only the first step.

“We walked into this and didn’t really know much of anything about education.”

But soon they had a dozen students in the first classroom.

“So we put third, fourth, and fifth grades all in one classroom.”

“And then we built the next building, and then that’s where sixth grade went. And then we built the next building, and that’s where seventh grade went.”

“We hired local teachers. Of course, first we had to file the paperwork with the Ministry of Education in Guatemala to become a legally recognized school.”

Matthew realized the traditional model of education was based on memorization, and he wanted to do more. So he went back to school and got a master’s in the philosophy of education.

Hero School is born

And after a great deal of research, “We came up with the concept of Hero School. Hero School is an amalgamation of what I thought were the best ideas that philosophers had come up with over the years. And so now our students are using their subject matter to fight poverty.”

The idea was to weave green building and community development into a hands-on curriculum.

“We figured out that the number one reason people go to the health clinic is because of upper respiratory infection, because they cook over open flames indoors. No chimney. And a house filled with smoke.”

“So we said, okay, seventh graders, let’s build a stove for a family.”

So in art class, they worked with clay and popsicle sticks to design a stove.

“And the students do it, right? So, they’re cutting red bricks, they’re cutting cinder blocks, they’re mixing cement, and they’re packing tires.”

The result was a more efficient and ventilated stove that could be replicated easily.

Long Way Home has built many projects including buildings, retaining walls, stoves (check out this cob ovencob ov), water collection systems and waste management.

Local labour

Building Earthship-inspired buildings out of trash is quite labour-intensive, which also helped the community.

“We were able to hire a whole lot of locals. At one point, we had 30 locals on our green building team, and they’re essential to the entire process, right? Because we’re from the U.S., and the locals know how to source everything,” says Matthew.

We’d say, “Hey, locals, where’d we come up with 25,000 tires to build our campus? And they go, “Okay, let’s get a flatbed truck. Let’s drive it along the Inter-American Highway. We’ll find local mom-and-pop tire shops. And we picked them up five, 10 at a time.”

They also source sand, cement, and rebar from the community.

Eco-social tourism volunteers

“Then, on top of that, we invited volunteers from all over the world, and we’ve had five, six, 7,000 volunteers who had an interest in sustainable living techniques. And they joined our local crew.”

It turns out the people who volunteer as eco-social tourists are “some of the best, most amazing people in the world too, because on top of the obvious engineers, architects, builders, there’s also teachers and administrators, and they helped us put the entire organization together, build all the classrooms.”

“The people that volunteer pay us $85 a week. And we also work with service groups who pay us. And the money that the people pay us to learn sustainable living techniques and to help us out on our campus goes directly back into the construction of the campus and to pay all of our teachers,” says Matthew.

Many of those volunteers were so impressed with the work Long Way Home was doing that they became board members and donors.

Built from trash, powered by people

Then, in 2023, Long Way Home received some well-deserved recognition for its work.

“We won the Education for Sustainable Development UNESCO Award. And that helped a lot.”

Matthew and Long Way Home have also taken their model of community development to South Africa and countries around the world.

“It all works well together because when you get out there, and you’re pounding tires together and you’re building a campus, there are friendships made that last a lifetime.”

It’s a message desperately needed in today’s fractured world, riddled with social fractures.

“A lot of people care about other people, especiallywhen they fly into Guatemala, do a little work with us out in the field, and then they can care about Guatemala for the rest of their lives. And there are a lot of wonderful people out there.”

Long Way Home operates its programs on a lean budget and receives support in the form of individual donations, grants, support from service organizations and some contracting work. You can get involved by volunteering and support their work financially as well.

Green Energy Futures CKUA Radio Podcast

Subscribe today for more than 400 stories! Here are parts 1 and 2 of our series on Hero Schools in Guatemala.