By David Dodge & Dylan Thompson

Brown gold. Prairie pies. Monkey missiles. Whatever you call them, they’re all over the place in Feedlot Alley near Lethbridge, the food processing centre of Alberta.

Where you or I may turn up our noses at a pile of ripe, smelly manure, Stefan Michalski, director of operations at Lethbridge Biogas, sees a resource that can be turned into clean, green energy.

Stefan Michalski came to Alberta from Germany more than a decade ago with a dream: to tap the back-end of Alberta’s agriculture industry and spin green energy from brown waste.

While biogas is relatively new to Alberta, it’s very common in Germany.

“As of today, there are more than 8,000 plants in Germany alone,” says Michalski. “It is a proven technology. It works even in Canada’s climate, which we have a lot of sceptics always asking about, and it has been around for decades in Europe.”

Recipe for turning brown waste into green power

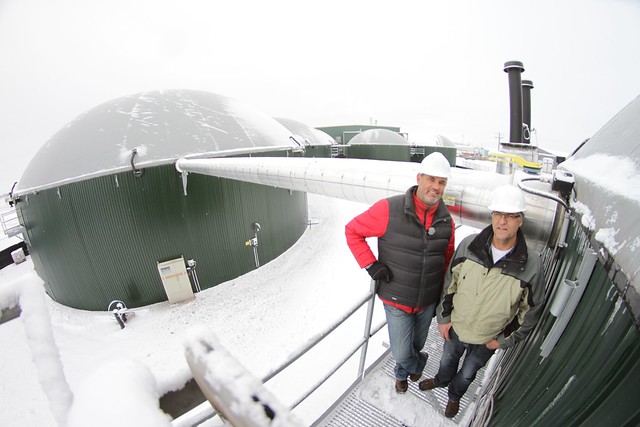

Stefan Michalski (director) and Ed Mulder (plan manager) on a catwalk near the top of the last storage tank in a chain of three 3.9 million litre biogas digesters that harvest methane from manure and organic good wastes. The methane is then burned to generate clean electricity. Photo David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

Normally, manure is spread on farmland as fertilizer, but this can pollute water, cause odors and release tons of greenhouse gases. Food waste is usually simply landfilled, which costs money and, like manure, releases plenty of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Lethbridge Biogas takes the manure and food waste, mixes it together, heats it to 39 degrees Celsius and captures the methane to power twin 1.4-megawatt generators, producing enough power for 3,000 homes.

The 3.9-million-litre digesters resemble giant, squat grain silos with dome tops. While it’s easy to make jokes about cow manure, it’s an essential ingredient for making biogas.

“Manure from a process perspective is a very valuable input material because it carries the form of bacteria you need, but it is actually very low in energy,” says Michalski. “So if you can balance that out and add organics that are higher in energy content, you can create an ideal mix with a higher output that manure couldn’t deliver.”

Turns out food waste is very high in energy. It really makes you wonder about our wasteful society when you see the food being dropped off (we saw vegetables, dog food, buns, coffee grounds and some messier stuff), but at least it’s better to turn this food waste into biogas than to dump it in a landfill.

Lethbridge is a food production hub, so there is plenty of organic waste from potato and vegetable processing as well as from local restaurants and stores.

“Typically, we are cheaper than the landfill which is an incentive to do it here, not only because it makes more sense, but you want to create some diversion with an economic incentive,“ says Michalski. Many places in Europe have banned organic waste from landfills, thus ensuring the waste is used.

So how does Lethbridge Biogas make money?

A truck of mature slurry unloads at the Lethbridge Biogas plant. The manure is mixed with high energy organic food waste and Lethbridge Biogas cooks the waste, harvests methane gas and then generates clean electricity with the gas. Photo David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

“First and foremost, we make power. Power still makes up about 60 to 70 per cent of our revenue stream,” says Michalski.

In addition to selling electricity, Lethbridge Biogas also collects tipping fees for organic wastes, which provides 20 per cent of its revenue. The final 10 per cent comes from selling carbon offsets.

“It is a small piece now but with the recent announcement of carbon tax and other initiatives around the Climate Change Leadership Plan, we think this is a piece that can grow,” says Michalski.

Reducing pollution

Producing clean energy from waste is pretty cool on its own, but biogas production also helps cut pollution in several ways.

When farmers spread manure in the fields, it releases methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. It can pollute local streams and runoff — and let’s face it, manure stinks.

The biogas production process takes the methane out of the manure and burns it to produce electricity, which reduces emissions by more than 90 per cent. Digestate, the leftover solids from the digestion process, is an even better fertilizer than manure, with fewer odors and significantly less pollution.

“[The farmer] has a product now that doesn’t stink as much,” says Michalski. “A product that’s better balanced, that has a better nutrient and phosphor-nitrogen ratio. He can deal with it the same way he dealt with the manure before.”

Lethbridge Biogas collects organic waste from restaurants, stores and food processors and mixes that with cow manure and then cooks it at 39 degrees celsius in a large “digester” that produces methane gas which is burned to generate electricity.

Lethbridge biogas collects the manure and returns it as a better product. “So for [the farmer], it’s almost a no-brainer because he has to do nothing,” says Michalski.

Most biogas applications are smaller than the 2.8-megawatt Lethbridge Biogas power plant, making them perfect for farm scale and a great tool for economic diversification. James Callaghan has 250 head of dairy cattle in Lindsay, Ontario and he built a farm-scale digester and a 500-kilowatt power plant. Ontario has almost 30 farm-scale biogas plants. Michalski says there is room for hundreds of the same in Alberta.

A place for biogas

Michalski says the biggest hurdle to developing a biogas industry in Alberta is the patchwork of regulation currently in place. Thanks to red tape and uncertainty, it took Michalski and his partners the better part of 10 years to get their plant going.

“We need a place for bioenergy and biogas, in particular,” says Michalski. “We need some regulatory mechanism and incentives to get there.”

Michalski thinks biogas should be recognized for its special benefits of not only producing base load green power, but solving a handful of environemental problems and creating economic diversification at a time when people are hungry for it.