By David Dodge and Kay Rollans

It all started with birdseed

When I first met Kent Rathwell, the CEO of the birdseed company Sun Country Farms, almost 10 years ago, he said something that, at the time, sounded positively audacious to me: “I wanted to prove that you could have a zero-emission company, in Saskatchewan, and still be sustainable.”

Rathwell and his wife bought Sun Country Farms after moving to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan from Toronto. Sun Country Farms operates out of an old grain elevator in Langham, Saskatchewan, northwest of Saskatoon. You see entire aisles of his birdseed and feeders in stores across Canada.

A lot of people didn’t believe that the zero-emissions endeavour would be successful. They said that Rathwell couldn’t do it—but in the end, he and his team not only proved them wrong, but went the extra mile. “We did that,” said Rathwell, “and we also did the whole value chain.”

In short, Rathwell created a carbon-neutral supply chain. He secured emissions-free electricity in a province that, then as now, was dominated by coal. Then, he created a upcycled an old cleaning plant, replacing the truckloads of coal it used to fuel its operations with biomass.

“There hasn’t been a truckload of coal there for years,” Rathwell said, adding that, eventually, he even started using his own off-grade oil seeds to make biofuels for delivery trucks.

From to birdseed to electric cars and beyond

But that’s just the beginning. Over a decade ago, Rathwell discovered Tesla while reading a popular science magazine. Tesla had their famed original Roadster on the road at that time, but its future was very uncertain. Many shied away from what, at that point, seemed like a risky business venture. But Rathwell? He was instantly smitten.

“That’s why I went down to see them. And after I drove the [Tesla], I was like, this is amazing and everyone needs to drive this and it only costs ten dollars to fill it up. And I can go faster than virtually anybody. It’s amazing,” he said.

While Elon Musk was putting every last penny he could find into Tesla, Rathwell got down to solving the obvious problem: Where do you charge these vehicles?

“No one [had] really put in the infrastructure so vehicles could travel. So then I immediately went home and cashed out and put everything I could together and dumped it into Tesla stock,” said Rathwell.

Though his stocks didn’t make him a fortune—he sold before the stock shot through the roof——his passion for electric transportation persisted. With his stock proceeds, Rathwell created a new company called Sun Country Highway and built a network of electric vehicle chargers across Canada.

Rathwell used his stock proceeds to literally give charging stations away to companies and municipalities along the route that agreed to pay for their installation and to allow the public to use them for free—and all this at a time when there were very few electric vehicles on the road. But Rathwell was invested in the long game: ensuring a secure future for electric vehicles.

Audacious? Yes. Some might say even a little reckless. But again, he pulled it off. Sun Country Highway took less than a year to install charging stations across 10,125 km of Canadian roads: the world’s longest green highway.

Rathwell then took his Tesla Roadster on a tour, crossing the country for free using the charging network they built—showing, in short, that it could be done, and done in style and done with an electric car in the depths of a Canadian winter.

In the intervening years Rathwell has added other carbon-busting products to his line, including biochar (a carbon-sequestering soil amendment) and zero-emission fertilizer and kitty litter.

An elephant in the room: Negative emissions and climate change

While Rathwell really hit his stride when he started Sun Country Farms, his passion for zero emissions began back in engineering school. He realized that the world was not being designed in a sustainable fashion. “What we had was completely and utterly and economically, socially, and environmentally unsustainable.”

It has taken the world more than 30 years to begin to appreciate the gravity of the climate crisis as the most serious existential threat humanity has ever faced.

In response to the crisis, most countries around the world signed the Paris Accord in 2016, pledging to work to minimize the damage of climate change by keeping the global average rise in temperature to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

While it was countries that signed the accord, it is all too often cities and municipalities that are leading the fight, declaring climate emergencies, coming up with climate and energy transition plans, and pledging carbon neutrality by 2050.

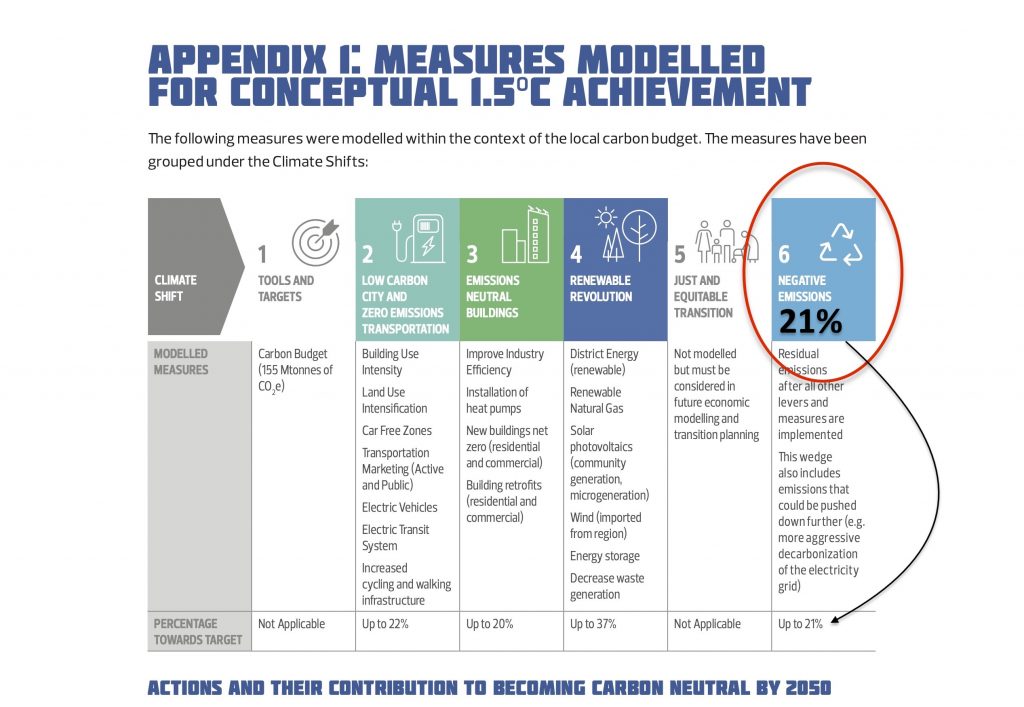

Cities like Copenhagen, New York, Paris, Vancouver, Edmonton, Halifax, and many others now have sophisticated plans that lay out the steps needed to stay within the 1.5-degree threshold. Edmonton even called their initial report “Getting to 1.5 Degrees.”

Through modelling and research, climate scientists have learned that we need to do just about everything to contain the scourge of climate change. Buildings need to be carbon neutral, transportation needs to be emissions free and energy supplies need to be renewable.

As it turns out Rathwell’s zero-emissions projects are big steps towards these zero-emissions visions. But there’s a problem: Even if we do all that, most modelling suggests it won’t be enough.

To achieve the 1.5-degree goal—we need negative emissions. That is, we need to find ways of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Reports suggest that Edmonton, for example, will need to achieve about 22 per cent of their reductions through negative emissions strategies.

Carbon sequestration and tree planting are existing negative-emissions options, but few if any plans detail how they are going to do this. At the end of the day, negative emissions strategies are a gaping black hole in energy transition and climate plans.

Cities know this – we need negative emissions to get to the critical 1.5-degree threshold. Kent Rathwell has a new big idea – a way to fill this black hole in climate plans around the world.

He calls it Carbon Plunk – the idea is to plant trees and combine this with carbon sequestration and plunk carbon back into the Earth whence it came. NEXT WEEK we plunk some carbon with Kent Rathwell in part II of our series on Carbon Plunk.