By David Dodge and Duncan Kinney

Kalundborg is a small port city in Denmark with a 12th century cobblestone downtown and a decidedly industrial feel. It is home to a 1,500-megawatt monster of a coal burning power plant, a refinery, a pharmaceutical plant, a plasterboard factory and a half dozen other paeans to steel pipe and smokestacks. Yet it’s here in Kalundborg where the future of industrial society lies.

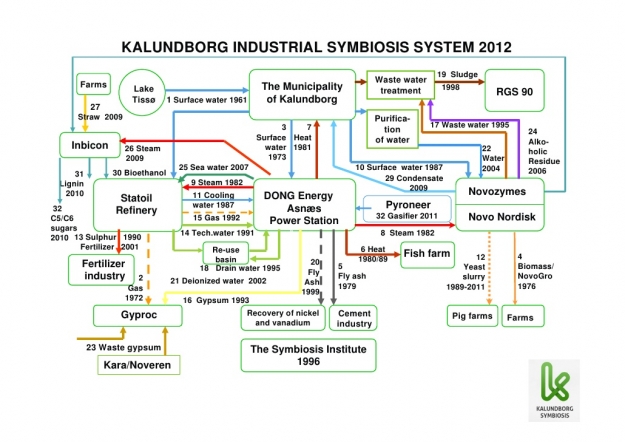

It’s called industrial symbiosis and it all started with their giant coal-fired power plant. Alongside all of those megawatts is excess steam, heat, gypsum and waste water and every single one of those byproducts have found a use in a complex ecosystem of industrial facilities around it.

At the centre of Kalundborg’s spider web of intertwined industrial facilities lies the DONG Energy Asnaes Power Station, a 1500 megawatt coal fired power plant. Kalundborg is the birthplace of the idea of industrial symbiosis.

At the centre of Kalundborg’s spider web of intertwined industrial facilities lies the DONG Energy Asnaes Power Station, a 1500 megawatt coal fired power plant. Kalundborg is the birthplace of the idea of industrial symbiosis.

Corn fuels cars, cows and tomatoes in Ontario industrial ecosystem

And it’s in this vein that we headed to Chatham, Ontario to see industrial symbiosis in action. Our catalyzing project in this case is Greenfield Specialty Alcohols, formerly called Greenfield Ethanol. It’s a first generation ethanol plant, a biorefinery that uses corn as a feedstock to produce 200,000 million litres of ethanol a year. Their production is split evenly between ethanol that is mixed with gasoline for vehicles and industrial ethanol, which you find in everything from shaving cream to vodka.

This refinery doesn’t just produce ethanol however, it kicks out a cornucopia of byproducts which they’ve found a number of uses for.

“Corn is a wonderful product because from corn, after the ethanol is made, with the sugars and starches that we convert there is a whole series of products that come from the fermentation,” says Angelo Ligori, the plant manager at Greenfield.

Greenfield sells 140,000 tonnes of distillers grain, the leftovers from the ethanol fermentation process, as animal feed. There is a Praxair carbon dioxide facility onsite capturing and selling 100,000 tonnes of CO2 a year. Greenfield even produces 3-4,000 tonnes of industrial corn oil that is sold as a feedstock for animals or biodiesel feedstock.

But Greenfield has one more untapped waste stream. The plant’s smoke stack is a landmark in Chatham, Ontario and every day waste heat from drying their distiller grains shoots right out into the atmosphere. It turns out there is enough heat coming out of that smoke stack to provide the majority of the heating for giant greenhouse next door.

Fresh green tomatoes – from the smoke stack to your table

When you walk into the Truly Green greenhouse the smell of tomatoes is heavy in the air. When I comment on it, Greg Devries, the president of Truly Green quips: “You like tomatoes? The right answer is yes. Everybody loves tomatoes.”

The greenhouse is huge, 22.5 acres with plans to expand to 90 acres and it’s chock full of green tomatoes on the vine that will ripen up shortly. Truly Green is slated to produce 5.85 million kilograms of tomatoes this year in this new building which has only been growing tomatoes since July of 2013.

Their location across the street from Greenfield is no accident. The plan is to take nearly all of the waste heat and leftover CO2 from the ethanol plant and use it to grow tomatoes. There are pipes underground that will bring hot water over to a heat exchanger and send cold water back on a loop. They expect to turn this system on in the next 12 months.

While Truly Green is currently running two 1.25 megawatt natural gas boilers when they turn on the waste heat project it will cut their heating costs by 50 per cent. And when heating is 40 per cent of your total expenses that really helps the bottom line.

“It’s really a feel good story on a whole lot of different fronts,” says Devries as he explains just how tangled this amazing spider’s web of industrial integration is. Devries family farm operation is called Cedarline Farms and they produce corn, soybeans and wheat and they have a small beef feedlot operation.

The family farm sells corn to Greenfield Specialty Alcohols and buys distillers grain back to feed their cattle. Now they will take the heat and CO2 produced from making ethanol out of their corn to heat the Truly Green Farms greenhouse and to improve their tomato yield.

“Anytime I am going down the road and I see a stack coming out of a processing plant and I see steam coming out of it I say there is probably an opportunity somebody should be looking at,” says Devries.

Looking at smokestacks as opportunities instead of eyesores is how an industrial society thrives in the future and it’s also how you grow a greener, more energy efficient tomato.