This article was written for and first published by The Earth & I magazine and is adapted and reprinted here with permission.

By David Dodge, GreenEnergyFutures.ca

Janna Greir always loved the idea of ranching, living in the country, and operating a small farm, but becoming a first-generation farmer is nearly impossible these days.

“My husband (Ryan) and I are both from Vancouver Island,” says Greir. “We didn’t grow up on farms; we’re first-generation, but we knew that we had an interest in agriculture.”

Janna is a registered nurse, and both she and Ryan worked in the city.

“We started with a small acreage with a few animals and quickly grew a passion for it and a passion in particular for sheep.”

After Ryan found work in Alberta, they bought Whispering Cedars Ranch, just outside of Strathmore, Alberta.

Then Janna discovered “solar grazing” from some friends who were doing it in Ontario. By coincidence, Capital Power was building a solar farm just outside Strathmore, Alberta, just a short distance down the road from their ranch.

Janna and Ryan had done their homework on solar grazing, and despite that agrivoltaics is still fairly new in Alberta, Janna approached Capital Power in 2021, and “they were just as excited about it as we were.”

Suddenly, these first-generation farmers were in business

“It’s created this unique partnership where it’s allowed us to grow,” says Janna. “At one time, we only had one sheep and then 10 sheep and then 60 sheep and 100 sheep. And now we have 600 breeding animals,” says Janna, whose flock now numbers 1,000 sheep.

This is all made possible by two intersecting needs.

Capital Power needs to control vegetation on their solar farm, and the Greirs need range and forage to graze their sheep.

Since taking an interest in solar grazing, Janna has developed significant expertise in vegetation management, improving soil quality, and planting the right species to improve the land and growth of her sheep.

She now owns Solar Sheep Inc. and is doing consulting for the solar industry, procuring custom seed mixes, all while expanding her own ranch operations to other solar farms.

The Strathmore Solar project is 41 megawatts on a total of 320 acres, 240 acres inside the fence and another 80 acres outside the fence.

Greir has a contract to manage the vegetation, inside and outside the fence, of the solar farm.

In the first year, Greir ran 400 sheep in the solar farm; just a few years later, she supports 1,000 sheep on the solar farm, and there’s room for more.

“The sky’s the limit with this site in particular because the vegetation and the way that it’s managed allows it to rebound so quickly.”

It wasn’t long after our visit with Janna on the Strathmore Solar Farm Janna confirmed she’s closed another deal, this time with ATCO to manage the Empress Solar Farm where she will run another 540 sheep.

Solar on Janna’s farm

We had to ask if Janna has solar on her ranch. “It’s funny you should ask that. We have a 28.8-kilowatt solar [system] very similar to this,” says Janna. “We put it in last year, and essentially, that brings our farm to net zero.”

Turns out the sheep at the ranch like the solar. Sheep are lambing beneath the solar modules, which protect them from sun, heat, wind, rain, and snow.

Pigs and solar

The success with sheep has inspired Janna to branch out into other species. As she walks behind a row of solar, we see pigs grazing beneath the solar.

“These are a specific type of grazing pigs. They’re called Kunekune and they come from New Zealand.”

These pigs have upward-turned snouts, and “They are not like traditional pigs where they root up the ground and they dig for all kinds of things.”

“The idea is not only to adapt and to allow for multi-species grazing, but the cool thing is when you’re running more than one species of livestock, they eat different plants.”

The pigs eat things left behind by the sheep, including the parasites and worms left by the sheep, which interrupts the life cycle of the parasites.

When we visited the solar farm, Janna had just learned her pigs were pregnant, so they expect 50 or more pigs to be grazing on the solar farm next year.

Agrivoltaics is farming squared

Greir jumped at the chance to join the board of the new Agrivoltaics Canada organization set up to create awareness, provide education, influence policy, and “Take agrivoltaics to a whole new level,” says Janna.

“Canada is just in its infancy with regard to agrivoltaics. We’ve only just got our foot in the door,” says Greir.

“There’s tons of room for food production under solar. That could mean anything from grazing to crop production – they’re even looking into berry production under solar, and specific types of gardens.”

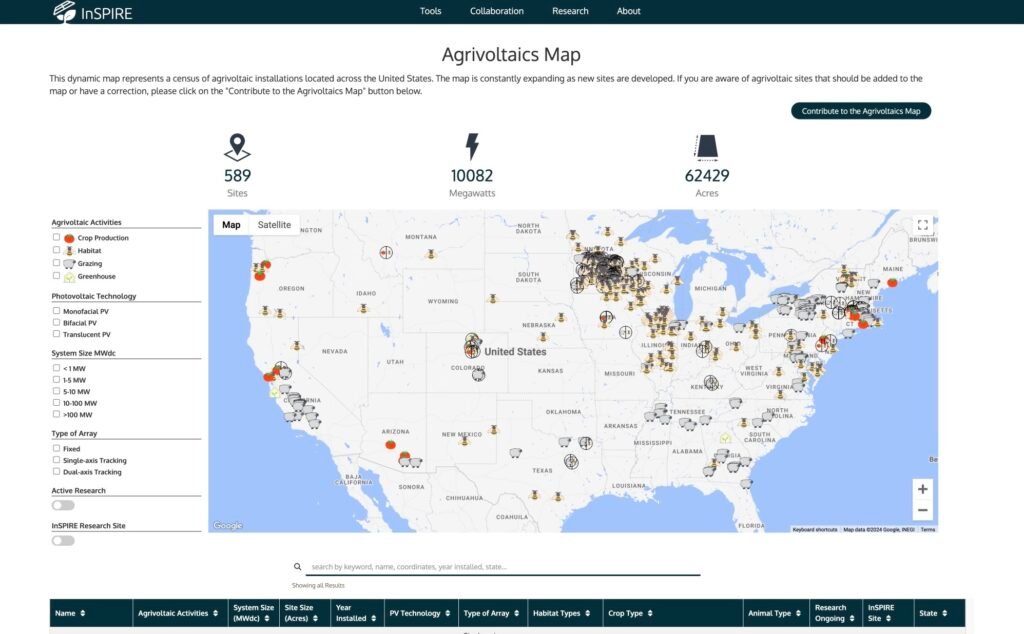

In the U.S., the Inspire Project, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, has mapped 589 agrivoltaic projects around the U.S.

Inspire tracks projects with crop production, habitat improvements, grazing, and greenhouse operations.

The state of Minnesota is a hot spot in the U.S. where sheep grazing is the most common application, although increasingly garden operations are emerging on solar farms.

Inspire also has created the Agrivoltaics Calculator to help evaluate low-impact solar development strategies.

Back in Janna’s home province of Alberta, Claude Mindorf was a founder of Agrivoltaics Canada, and a former farmer who now works with solar companies.

He’s jazzed about the potential of agrivoltaics and is keen to educate farmers on the potential, and he’s working on various models of farming integration.

He’s working with Shawn Morton, a fourth-generation farmer from Joffre, Alberta, who runs a cow-calf operation and partners in various farming operations as well.

Keeping the family farm in the family

When Shawn was first approached with the idea of solar on his land, he did what farmers usually do: “You always say no,” says Morton.

But the solar guys were patient, and eventually, he met Claude Mindorf, and today he has a 48-megawatt solar farm on his land. And part of his deal with the solar developer is to continue farming and grazing on the lands.

“If we can continue to use it in agriculture, I think the benefits are tremendous,” he says, standing between two rows of solar modules on his farm. Initially, he intends to hay the site and eventually run a herd of sheep on it.

“I think the benefits are tremendous. As you can see up and down these rows, we’re in the middle of May and already the grass has grown probably four inches,” says Shawn, adding there was no impact on the quality of the land.

“I hope that my daughter will farm, or if she doesn’t choose a career in agriculture, she’ll have the benefit of being able to stay in agriculture with the revenue from the solar park.”

Shawn Morton, Farmer

More significantly, these new revenues from the solar lease have transformed his thinking about farm succession and his young daughter.

“There’s a financial benefit. I think it’ll keep a lot of farmers on the land,” he says, adding “I’m able to farm full time with the financial benefit of the [solar] park.”

“I hope that my daughter will farm, or if she doesn’t choose a career in agriculture, she’ll have the benefit of being able to stay in agriculture with the revenue from the solar park.”

This is music to the ears of Claude Mindorf, who explains there are essentially three kinds of agrivoltaics.

Three kinds of agrivoltaics

“Field agrovoltaics, where you have cereal grains. There are designs for vertical panels where you can grow tall crops like corn, grain, and canola in between.”

“Then there is what we call the market garden approach,” where the solar canopies almost touch at the top or they are V-shaped and almost touch on the sides. “They provide shade and shelter for tender fruits like strawberries, bench strawberries, blackberries, blueberries, or haskaps.”

He says you can also grow leafy vegetables. “Any of the nightshades, potatoes, beets, tomatoes, or peppers grow incredibly well under solar.” Mindorf says there is plenty of research going on in this area in Oregon, Arizona, and other places.

“The third is what you see here [at Joffre]; where you have single ground mount panels or single axis tracking where grazing is the primary activity underneath and then you rotate crops in every few years to reduce the site becoming root bound.”

But isn’t solar gobbling up farmland?

Contrary to the most common refrain (myth) about solar gobbling up farmland, Mindorf says Dr. Joshua Pierce of Western University in Ontario found it would take “less than 1% of the agricultural lands, under utility-scale developments such as Joffrey” to “provide Canada’s electricity,” says Mindorf.

This was confirmed in Alberta where solar was booming until the provincial government slammed the brakes on it with their big “renewables pause.” One of the reasons cited was to protect farmland.

But the province’s own Alberta Utility Commission found in a January 2024 report that solar and wind projects would take up less than 1% of farmland by 2041.

Solar rarely, if ever, goes on class one farmland because farmers already know the best use for that land.

Agrivoltaics can help improve the quality and productivity of farms.

In many cases, the quality of the farmland and productivity is increased in agrivoltaics. As ranchers such as Janna Greir bring their expertise to vegetation management, soil quality and biodiversity improve.

And with growing expertise, innovation is coming fast.

After just a few years, Janna Greir has some ideas for solar farms that use trackers with drive shafts for and above-ground cabling for solar tracking modules.

With slightly different spacing and the placement of some of these mechanisms and cables out of the way or underground, solar farms could drastically improve the potential of the land.

“For instance, we could come early in the season, and we could hay it. And we’d have extra forage for our animals throughout the winter,” says Greir. In the northern climate of Alberta, her sheep can stay on the solar farm from May until the end of November, but in the winter, they must be fed back at their ranch.

“We’ve got forage for animals for six, seven months of the year on the solar farm,” says Greir. “But feeding them for those additional six months is extremely expensive.”

This is thanks to climate-enhanced droughts and other factors.

“Being able to produce forage and/ or crops underneath solar that you could continue to use it for your operations at home throughout the winter.”

“That would be a game changer, for sure.”

Greir says they’re learning, the solar companies are learning, and just by changing their mindsets just a little bit could improve things drastically for the farmer.