The Municipal Climate Change Action Centre

Municipalities Taking Climate Action – Part III

Just as Pincher Creek was hauling water to town, Edson declared a state of local emergency after 135 mm of rain fell. Entwistle was evacuated for fires and floods in the same year.

Climate adaptation photo gallery

What’s a small town or city to do?

As we learned in the first two stories of our Municipalities Taking Climate Action series many communities are doing energy efficiency projects, installing solar and electric vehicle chargers. This is called climate mitigation, actions designed to reduce emissions causing climate change.

Climate adaptation on the other hand refers to understanding the risks of climate impacts and adapting to avoid some of the bigger impacts.

The trouble is climate adaptation has always seemed like a future-oriented endeavor, but now with disasters hitting communities hard it has become an imperative.

The Municipal Climate Change Action Centre (MCCAC) knows this so they’re helping fund work to assess risks and prepare plans in 49 projects involving 66 communities in Alberta.

“These communities are all working on climate adaptation plans, which tell them the risk, what is the likelihood of climate events happening and what are the consequences when those events happen,” says Ronak Patel a program manager with the Climate Resiliency Capacity Building program a the MCCAC.

Climate Resiliency Capacity Building program

Pincher Creek is quite familiar with some of the risks.

Tristan Walker in the energy manager for the town and municipal district of Pincher Creek. He took us to a viewpoint over the Oldman River.

“As you can see down below us, there’s not much water left in the reservoir. The freshwater intakes themselves are above water, which means that we’re having to truck fresh water continuously to our water treatment plant to supply our residents with their drinking water,” says Walker, adding “It costs thousands of dollars a day.”

Then he took us down the road in the county to Waterton Lakes National Park where a massive fire burned in 2017 stretching resources in the county and sending smoke everywhere.

Fires, smoke drought and heat are concerning residents

Pincher Creek was one of the communities that signed up for financial support to assess the risks and draft a climate adaptation plan for their town and county.

“The goal with this plan was to really engage with stakeholders in the area and understand what their perception of the risks were and then to get data to back that up,” says Walker.

They hired the One Sky Foundation to assess the climate risks and help prepare a climate action plan.

Pincher Creek also invited the Piikani First Nation to participate in their process and Tawnya Plain Eagle says thanks to their familiarity with the land they brought an environmental perspective to the planning process. The Piikani Nation is also preparing its own climate adaptation plan.

Perhaps ironically many people don’t worry too much about these impacts until they experience them.

Tawyna Plain Eagle of the Piikani First Nation says her people started waking up to concerns about climate impacts last summer when their community was plagued by smoke from Alberta’s record wildfire season.

“One of the sad things that I’ve been seeing is people looking forward to summer being over because they don’t have to deal with smoke and they don’t have to deal with, you know, the bad air quality,” she says. This combined with the drought and extremely low water levels at the Oldman Dam have people concerned.

The detailed One Sky report predicts 15 more +30C days per year, higher annual precipitation and more frost-free days.

Love climate change, except for the impacts

This sounds pretty good until you realize the extremes in drought, fires, floods and weather events are quite damaging.

“Both wildfire risk and wildfire smoke risk were large potential risks,” says Walker. “Drought is a potential risk as well,” he says adding this is predicted to negatively impact winter recreation in the area.

Most pressing for Pincher Creek is dealing with the water shortage situation caused by drought. The report included 38 recommendations for climate adaptation actions.

Walker says they are already taking action on things they can afford to do. They are working on heat, smoke and emergency plans as well as coming up with infrastructure changes that could help manage or reduce the risks.

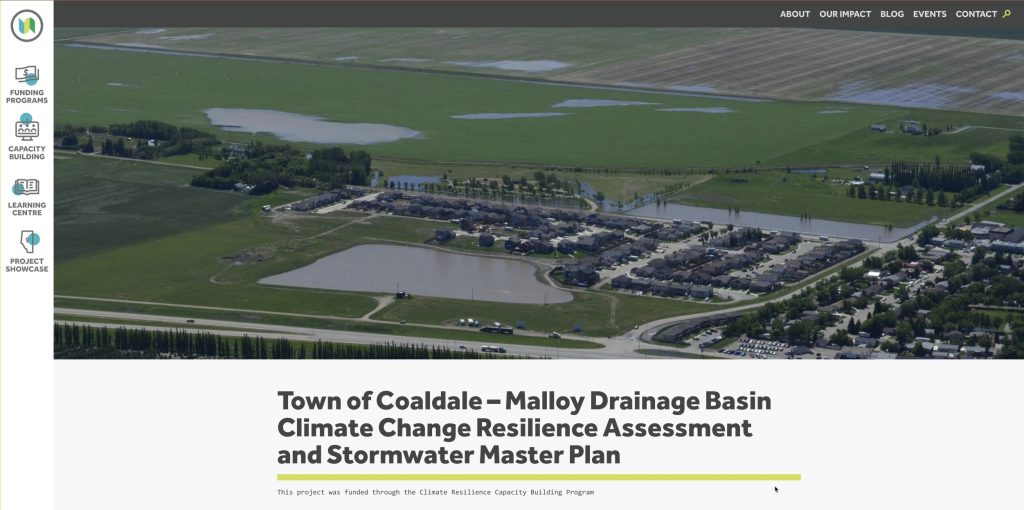

Pincher Creek installed backflow prevention valves in some of their stormwater outlets to prevent flood waters from heading back up the pipes into town, as an example.

Double trouble – stopping emissions vs preparing for impacts

The report also assessed the economic risk of inaction.

“So, what we saw was $10 million in 2025, through to $18 million by 2030 and into $20 plus million by 2050 is the cost of doing nothing,” says Walker.

These costs are steep and getting steeper. A white paper from Senator Rosa Galvez’s office estimates the Canadian economy will take a $5.5 trillion hit by the end of the century thanks to climate change.

The Insurance Bureau of Canada estimates an investment of 0.2% to 0.3% of GDP is needed for Canada to adapt to climate change, a total expenditure of $5.5 billion per year.

The insurance bureau keeps close track of climate impacts and the financial damage they impose. In a 2018 story David McGown of the IBC told Green Energy Futures that Canadian insurers were paying out $400 million per year for damages due to snow, hail, wind and floods in the 1980s. In just ten years that number had climbed to $1 billion in losses per year and in 2022 the IBC reported $3.1 billion in payouts for severe weather events.

At $5.96 billion the Fort McMurray fire of 2016 is the highest-cost event in Canadian history.

It’s tricky because if we fail to mitigate the impacts of climate change by drastically reducing emissions these numbers will keep climbing. Some argue we are there already, but it won’t be long before we won’t stand a chance in hell of covering the costs of climate impacts.

The town of Lytton B.C. burned down in June 2021 and they are still trying to figure out how rebuild the town.

Budget pressures force strategic investments

Towns and cities have precipitously tight budgets and Tristan Walker back in Pincher Creek says “The projects that we do are always preceded by technical and economic analysis,” and they’re always “looking into the project and identifying how much it’s going to cost and what the payback is going to be.”

For emissions cuts the payback can be savings from using less energy or revenue from producing solar power. For climate adaptation, it’s avoided future costs, a very difficult thing to justify in municipal budgets.

But these 26 communities now better understand the risks and have a much better idea of where they can get the best bang for the buck.

Some like the City of Leduc partnered up with surrounding municipalities in the Edmonton Metropolitan Regional Board to conduct their risk assessments and adaptation plans.

To see stories about various municipalities check out the MCCAC website.

Sometimes the actions are pretty simple, such as installing back-flow values in your storm sewers.

Walker isn’t sure what Pincher Creek is going to do about their water crisis, but it’s right on top of the list of things local politicians and administrators need to solve quickly.