By David Dodge and Scott Rollans

Oil and gas may drive Alberta’s economy, says economist and author Mark Anielski—but the true picture lies beyond the conventional balance sheets.

Mark Anielski’s new book makes the case that well-being be treated as a key asset in modern economics.

Anielski is the author of a new book entitled An Economy of Well-Being: Common Sense Tools for Building Genuine Wealth and Happiness. In it, he proposes a “Genuine Wealth Accounting”—one that tracks natural resource liabilities as well as assets, and one that places tangible value in people’s overall well-being.

Alberta’s GDP tracks the monetary wealth generated by the petroleum sector, but fails to consider our unfunded liability of $13.7 billion for carbon pollution (based on $50/tonne). And that’s just the beginning. Our province has an estimated 155,000 orphaned wells, with remediation costs estimated at $8 billion. And there are other massive liabilities—such as the ever-growing oilsands tailings ponds, which currently cover over 250 square kilometres and hold nearly 1.3 billion litres of waste.

The unbalanced balance sheet

GDP, the conventional gauge of economic activity, treats natural resources as if there is an endless supply, and environmental impacts as though they are irrelevant. Economists may say they’re agnostic, tracking only the flow of money, but Anielski argues they’re wearing rose-coloured glasses. They ignore billions of dollars in environmental, social, and financial liabilities that will eventually bite us in the butt—and the wallet.

Anielski adopts a more comprehensive outlook: “Assets are things that contribute to your well-being … liabilities are things that put your well-being at risk.”

An economy of well-being

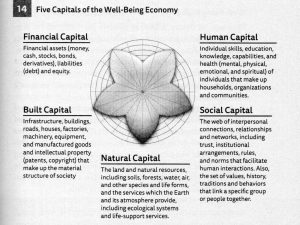

Mark Anielski says we must track five kinds of capital in order to create an economy of well-being.

An Economy of Well-Being serves both a critique and a reimagination of modern economics and accounting. “Wealth means the conditions of ‘well-being’ from Old English,” says Anielski. He advocates an accounting system that measures well-being, and properly tracks all assets and liabilities.

“You can’t operate a corporation without a proper balance sheet,” says Anielski. “So, how is it that governments lack a proper balance sheet for cities, provinces and nations—with the only focus being on GDP growth?”

Anielski has pioneered his Genuine Wealth Accounting approach in his work with cities and nations around the world. The “assets” sides of his balance sheets incorporate natural, human, social, built and financial capital. Then, he tallies the human, social, environmental and financial liabilities—include the cost of disease, depression, relationships, trust, belonging, and any damage to watersheds and ecosystems.

If you track the liability of carbon pollution, orphan wells and tailings ponds, you shift the needle on Alberta’s full economic picture.

Fortunately, says Anielski, you can take steps to shift the needle the other way, too. “What if we start to think, ok, maybe we should accelerate the investment in solar and net-zero homes. These are assets are going to deliver future long-term well-being, and also reduce liabilities.”

Measuring well-being is just good economics

Anielski has worked in Bhutan, a country that has a Gross National Happiness accounting system.

Money can’t buy well-being and happiness. They are our most valued assets, yet we don’t measure them. Meanwhile, few (if any) public policies are designed or tested for their effect on overall well-being.

Anielski says research in positive psychology has revealed the keys to a happy life: one’s upbringing and genetics (50 per cent); the quality of relationships with family, friends and work colleagues (40 percent); and income and education (a relatively small 10 per cent).

Had the government of the UK been using indicators of well-being, they might have seen Brexit coming. Starting in 2013 Gallop documented a sharp decline in people who described themselves as “happy” or “thriving.” Ironically this also coincided with rising GDP and very low unemployment rates.

In the US the Harris Happiness and Economic Performance index shows nearly an inverse relationship between GDP and happiness.

Anielski says perceptions of well-being can be measured, and need to be included as assets on the balance sheets of corporations, cities and nations.

Well-being reveals citizens’ return on investment for taxes

Valleyview has a new environmentally friendly passive house civic building–something Anielski has checks off numerous well-being boxes in a Genuine Wealth Accounting system.

Anielski helped create a well-being index for the small community of Valleyview, Alberta, population 1,800. “We asked everybody from grade six students all the way up to 80-year-olds to self-rate their well-being. We came up with the index for well-being for Valleyview, which now will help guide municipal governance and decision making.”

One insight generated by the study was that residents “didn’t really like the aesthetic feel of Main Street.” So, the town talked to business folks, formed the Valleyview Coalition, and now this group represents the well-being interests of the community. One simple solution: beautify Main Street.

The town also recently built the first passive-house municipal building in Alberta. Some of the additional costs will be recovered through energy savings. But, Anielski says the project also delivers significant well-being assets, including local pride, happier employees and improved employee performance.

Two big take-aways

Anielski leaves us with two big take-aways. First, he doesn’t expect governments to abandon conventional accounting practices. But he does believe their balance sheets should also reflect the well-being, integrity and long-term sustainability of our natural capital assets—and their social, environmental and financial liabilities.

Second, he asserts that well-being assessments represent much more than feel-good idealism. They can also shape public policy in some incredibly pragmatic ways.

What if governments actually knew what factors, big or small, are actually improving our lives? What if we decode the relationship between self-rated well-being of citizens and the operating and capital budgets of governments? What if we can increase the value we derive from taxes, through simple actions that make us happier as a society?

“We’re going to also affect the way governments manage their assets. It’s a so-called community asset management system. So, it’s not just about roads and pipes and water treatment systems. It’s about how people feel about their neighbours, how they get along, how they trust each other, how they perceive the natural environment.”

Mark Anielski is also the author of the award-winning The Economics of Happiness and the author of the new book An Economy of Well-Being.